FaceApp is cool again, and adamant it's not a privacy minefield

The company denies the conspiracy theories around it.

FaceApp, the image-editing app that can radically change how you look is back in the spotlight. And, as usual, questions about the company’s practices, motives and plans are sure to follow.

This is the third or fourth time that FaceApp has leaped into the zeitgeist, attracted press attention yet again. It’s the upgraded “gender” filter -- which aims to alter your gender presentation -- that often drives these conversations as people share their images online. Recently, a British tabloid gave “female makeovers” to the twenty Premier League Soccer managers, while actor William Shatner said that he’d “do” his female doppelganger.

(It should also be noted that the existence of the filter may be problematic if it’s used to trivialize the lived experience of trans people.)

Engadget sat down with Juggs Ravalia, Vice President of FaceApp Inc., a former Yandex executive and Microsoft alumnus who joined the company last year. (FaceApp itself is developed by a Russian company, Wireless Lab, Ravalia heads up the company’s US-registered subsidiary). He said that one thing that has driven improvements in the app’s filters was a new focus on, well, hair.

Ravalia said the company planned to add a tool that let people plan their post-lockdown haircut. But the knock-on effect is that all of the filters look a lot more natural and realistic than before, without the awkward bleeding into the background edited images used to have.

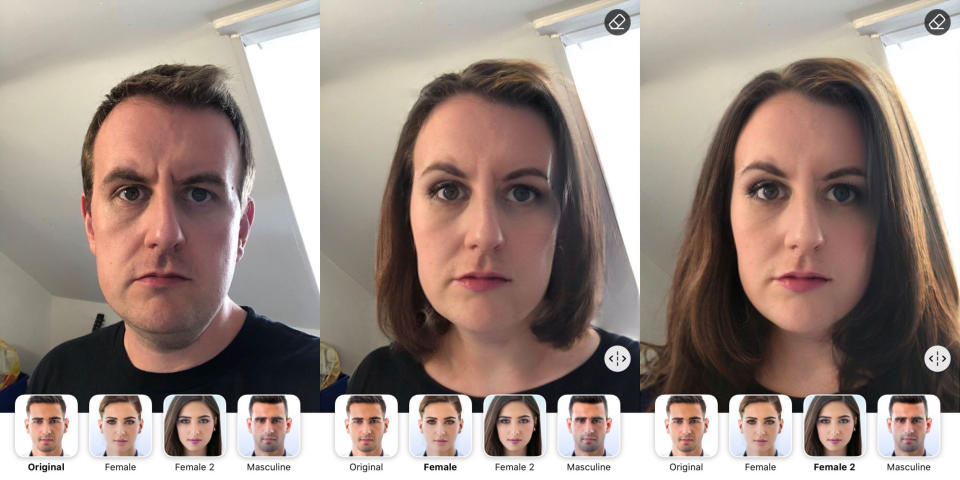

He explained that as well as making haircuts more realistic, the team worked on other subtle changes to improve the images. For instance, the gender filter also changes your clothes to suit an alternative cut. Look at the neckline of the t-shirt I’m wearing in the example below, which widens out during the filtration process. Similarly, a Reddit user by the name of Moonkikie pointed out that their filtered image now included chest hair.

FaceApp’s next frontier is bringing its image-editing magic to video, ideally to create live filters on top of videos. A limited version of this feature has already soft-launched on the iOS app, letting you try the old age and child-like filters free of charge. The clips are choppy and struggle to keep up if you move your head too much, but the result is still staggering. Currently, legions of VFX artists spend months aging and de-aging stars in movies, but that could all change.

“You’ve got 60 frames a second, you got 60 seconds a minute, [you’re] looking at 2,000 frames a minute,” said Ravalia. “If you’re going to retouch [all] that, you need to make masks and go frame-by-frame, it’s a two-to-three week job, but we want to do that [with] a single tap.” The preview videos are sent to a server to be processed, but in the future, the option could be available natively on devices.

Wherever FaceApp goes, political contortions about the nature of deep-learning apps and user-uploaded content follows. When the app spiked in popularity last summer, it quickly raised the ire of political operatives.

Bob Lord, Chief Security Officer at the Democratic National Convention, was quoted by CNN instructing party members not to use the app. “This novelty is not without risk: FaceApp was developed by Russians.”

Senate minority leader Charles “Chuck” Schumer even contacted the FBI to ask for its impression of the app. In a letter, which Schumer posted to Twitter, Jill C. Tyson, Assistant Director at the Office of Congressional Affairs, said that the FBI sees any tech, developed in Russia, as a “potential counterintelligence threat.” She went on to explain that because Russia has the power to seize data stored on any server in the country, anything FaceApp has, the government can access.

A warning to share with your family & friends:

This year when millions were downloading #FaceApp, I asked the FBI if the app was safe.

Well, the FBI just responded.

And they told me any app or product developed in Russia like FaceApp is a potential counterintelligence threat. pic.twitter.com/ioMzpp2Xi5— Chuck Schumer (@SenSchumer) December 2, 2019

It’s clear that any discussion of FaceApp will, inevitably, turn towards privacy and Ravalia said he expected the topic to dominate our conversation. He pointed to the company’s now very thorough privacy policy, which has grown considerably since the one published in early 2017.

Ravalia said that while there may be live previews on-device, the only image uploaded to the server is the one you choose. It is encrypted with a key that’s only held on your phone, “even if someone came to us asking for this photo, we don’t store the key.” He added that all images are “temporarily cached for 24 hours,” and if you don’t choose to re-edit the image in that time, it’s marked for deletion, which takes another 24 hours.

“Users should be more worried about the data the company openly collects, instead of worrying about a conspiracy to secretly siphon the world’s selfies.” - William J. Altman, SOSA

In response to the accusations that the images are being piped back to Russian soil, Ravalia reiterated that FaceApp uses Amazon and Google’s cloud servers. “We store encrypted photos at the regional location closest to the user or in the US,” he said. “For the US, it’s always the US, and for the EU users, it could be the EU or US.” “Anything that is stored on the server-side, whether that is Amazon or Google, is basically what we have. What we have on the client is basically nothing. Those are OS file objects, Google or Apple has much more control of that.”

Unlike almost every other social platform, FaceApp does not ask you to create an account. Ravalia added: “We don’t have a log-in, we don’t have a user ID to link people, we don’t do a lot of things that are associated with the user,” he said. “In our settings, we give users the option to delete their data, and that includes your push tokens, your subscription token, that -- in some jurisdictions -- could be personal data, so we delete it all.”

Building a toy app could be a very efficient way to source vast quantities of user data. Surely, if you can make something fun, you can use it to acquire a huge amount of free information that can then be used to train your deep learning models, right? “Absolutely not,” said Ravalia, “we solely use user’s photos for the editing functionality,” he said, “we do not use that photo for any other purpose, be it training, selling data, advertising, nothing.”

“We’ve done everything, product-wise, to make sure that we are doing things to abide [the law], and we want to listen to users and critiques,” he said.

Engadget contacted Bob Lord, who initially raised concerns about FaceApp’s security, who did not respond at the time of publication.

Given the horror stories around popular social media apps -- most recently involving TikTok, you may expect FaceApp to be terrifying. Engadget contacted numerous security researchers and businesses to ask for comment, but the results were surprising. Tal Bar, the CEO of security company Octopus, said “from a security standpoint and a high-level overview, we don’t see anything problematic on the device level but this requires further testing.”

William Altman is a Cybersecurity analyst at SOSA, a company that pairs startups with large companies and governments. He says that FaceApp “is not an overtly malicious application tricking us all into surrendering our data for nefarious reasons, at least right now.” He added that, as with all free software packages, “users should be more worried about the data the company openly collects, instead of worrying about a conspiracy to secretly siphon the world’s selfies.”

He added that the only other risk that he can see is how FaceApp collects your device’s metadata. “For example, the app can determine the computer and mobile device operating system, system type and version number, manufacturer and model, as well as IP address.” “While this kind of data is not directly harmful to users if exposed,” he added, “the fact that it is being collected does warrant further questions about FaceApp’s metadata-harvesting practices.”

On this point, Ravalia says that FaceApp’s main business model is to drive subscriptions to its professional suite. For a monthly, yearly or lifetime fee, users can get access to all of the app’s filters and effects, only a handful of which are available for free. And, so far, FaceApp’s made enough money to keep the company running. In comparison to a lot of other social platforms, FaceApp doesn’t spend much on advertising and instead hopes that the organic growth of filters draws the necessary attention.

Ravalia says that people who get lured in by a viral effect often keep subscribing long after. And it’s likely that debates about FaceApp aren’t going away any time soon.