The best WiFi router

The TP-Link Archer A20 is Wirecutter's pick as the best all-around router for speedy and dynamic connections.

By Joel Santo Domingo

This post was done in partnership with Wirecutter. When readers choose to buy Wirecutter's independently chosen editorial picks, Wirecutter and Engadget may earn affiliate commission. Read the full guide to Wi-Fi routers.

After testing 10 routers over 120 hours, we've determined that the best router for wirelessly connecting your laptops, your smart devices, and anything else your daily life depends on is the TP-Link Archer A20. It was faster than anything else we tested at both close and long range, it's reliable, and it shrugs off the stress of handling multiple wireless devices simultaneously.

The TP-Link Archer A20 tri-band 802.11ac router passed all of our performance tests with top marks. If you don't have a huge or complicated house that needs a mesh-networking kit, the Archer A20 is the best choice to replace an older router or one that doesn't have the range, speed, or reliability you need now. The Archer A20 has features such as a quad-core processor and band steering over its three channels (two 5 GHz and one 2.4 GHz), which can help you connect your household's growing collection of wireless devices while avoiding dropped connections and slowdown.

The Synology RT2600ac is a bit pricier than our pick, and it finished our performance tests in a dead heat with the Asus Blue Cave and Asus RT-AC86U for second place. It has a dual-core processor, rather than a quad-core, and it lacks a third wireless radio, which means it may reach its limits earlier than the Archer A20. You can extend the RT2600ac into a mesh network with the add-on Synology MR2200ac router; purchasing a mesh-router kit is often less expensive than buying two separate routers to create a mesh network, though, and many mesh kits have extra features, such as dedicated wireless bands, that help them perform better.

TP Link's Archer A7 router is relatively inexpensive, and it's a great choice for small homes or one- or two-bedroom apartments. TP-Link has improved the Archer A7 since we tested it in 2018, adding band steering (here called Smart Connect) and TP-Link OneMesh support via firmware updates. The A7 lacks beamforming and MU-MIMO, two high-end features that can improve speeds but aren't vitally important, but still performs well at shorter distances. On our toughest test it outperformed two higher-priced competitors, though the Archer A20 and other top performers still beat it overall. It's typically less than half the price of the Archer A20, and we think it's the best router you can buy for less than $100.

Why you should trust us

Before joining Wirecutter, Joel Santo Domingo tested and wrote about PCs, networking, and personal tech at PCMag.com, Lifewire, HotHardware, and PC Magazine for more than 17 years. Prior to writing for a living, Joel was an IT tech and system administrator for small, medium-size, and large companies.

Metaphorically, Joel has been a wire cutter for at least two decades: Testing wireless home networking has been a part of his life for the past 20-plus years through all versions of Wi-Fi, back to the wireless phone extension he tacked onto the back of his Apple PowerBook. He did that so he could connect to the Internet from his desk, his couch, and his bed seamlessly (a rarity for the time).

Who this is for

If you're happy with your Wi-Fi, you don't need a new router—it's as simple as that. If you're having problems with range, speed, or reliability, though, it might be time for an upgrade. An older router that doesn't support 802.11ac (also known as Wi-Fi 5), has a weak CPU, or lacks Gigabit Ethernet ports can hold you back significantly.

This guide covers standalone Wi-Fi routers. Any of our picks will easily outperform any router you got from your Internet service provider, or any router more than a few years old. These routers are a good fit for apartments or small to medium-size houses with three or four people on the network. If you have more people or a large house—more than 2,300 square feet or more than one floor—you should probably look at our mesh-networking guide instead. A good rule of thumb is that if you've considered adding a wireless extender or an extra access point in your house, get a mesh system instead.

What you shouldn't do is blindly buy either the cheapest router or the most expensive router you can find. Quality doesn't necessarily scale with price, and a router with a bigger number on it may not actually solve your Wi-Fi problems.

What you need to know about wireless routers in 2019

A typical home network in 2019 doesn't look like it did a few years ago. Without even getting into the explosion of smart-home devices (everything from smart light bulbs to doorbells to washing machines now expects a decent Wi-Fi connection), most homes these days have two or more personal Wi-Fi devices (phone, laptop, tablet) per person, as well as smart TVs or a streaming media box such as a Roku or an Amazon Fire TV. A busy evening in a typical home could have one person downloading game updates in a bedroom, a second listening to music from a smart speaker, a third watching TV in the living room, and a fourth browsing the Web sitting on the couch—and all of that traffic demands a router that can provide fast performance for lots of devices at once. That development has made us a lot pickier about what routers we accept as the best for the most people, and a lot more interested in features such as band steering and a third wireless band. These features cost more, but they're worth the expense.

Although all modern routers are at least dual-band—offering one slower but longer-range 2.4 GHz band and one faster but shorter-range 5 GHz band—it's not easy to take full advantage of both bands. On most cheap (or old) routers, you have to make two separate network names—such as "mynetwork2.4" and "mynetwork5"—and then decide which of your devices should join which network. If you don't give your networks different names (SSIDs), in practice all your devices end up piling onto one 5 GHz band, and you experience slower speeds, delays, and even dropped connections when several of them are online and busy at the same time.

Band steering—specifically load-balancing band steering—lets you use a single network name for all your Wi-Fi bands and allows the router to decide which devices go on 2.4 GHz and which ones go on 5 GHz based on where they are in your house and how much bandwidth they're using. Band steering is essential for mesh networks, which have multiple access points and multiple bands to deal with, but the feature is important even in standalone routers, because if you aren't using all the radios in your router, you aren't getting all the performance you paid for.

We tested this feature very carefully—unfortunately, some routers that are theoretically capable of band steering merely wind up connecting your devices to the "strongest" signal, cramming everything onto a single 5 GHz band again. Our picks are smarter than that.

Tri-band routers have an extra 5 GHz band in addition to the 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz bands of a dual-band router. This third band allows more devices to connect and be busy at once without slowing the network down so much. Load-balancing band steering becomes even more important with tri-band routers—that extra radio won't do you any good if none of your devices are connected to it. We used to recommend against spending the extra money on a tri-band router, but busier networks with more smart devices in more congested areas can definitely benefit, and the feature doesn't cost as much as it used to.

All 802.11ac routers come with an AC speed rating meant to tell you how fast the router is, formatted as "AC1900" or "AC2600," for example. The bad news is that AC speed ratings are really, really bogus. In the real world, AC2300, AC1900, and AC1750 all mean pretty much the same thing: a dual-band router with one 2.4 GHz radio and one 5 GHz radio, each supporting up to three spatial streams—concurrent connections that the router can combine to increase the throughput available to your device, similar to adding lanes to a highway. A rating of AC2600 indicates a dual-band router with four spatial streams each, and a rating of AC3200 means a tri-band router with three spatial streams each.

When you see a router advertised as 2×2, 3×3, or 4×4, those pairs of numbers refer to the number of transmitters and receivers the radio has, with which the router can communicate over the spatial streams. The kicker here is that the phones, laptops, game consoles, and other devices you're using are almost always 1×1 or 2×2 (so they support either one or two spatial streams, respectively), and the speed of the connection is determined by the device with the fewest spatial streams. A 2×2 laptop wouldn't get any more throughput from a 4×4 router than it would from a 2×2 router, though it would still get twice as much as a 1×1 laptop.

What about using those extra streams to connect to another device at the same time? For the most part, that's a no-go. You might have a 2×2 laptop, a 2×2 phone, and a 4×4 router—but unless all three of them support a technology called MU-MIMO, the router can talk to only one of them at once, using only two streams. With MU-MIMO, the router could talk to the phone using two streams and to the laptop using the other two, simultaneously. Right now, routers with MU-MIMO support are common but not ubiquitous; client devices with MU-MIMO are rarer than hen's teeth. So having MU-MIMO support—and more than three spatial streams—in your router is nice for future compatibility, but it isn't really a killer feature right now.

In October 2018, the Wi-Fi Alliance, an industry organization responsible for certifying that Wi-Fi devices work together, announced that it was rebranding Wi-Fi 802.11n as "Wi-Fi 4," 802.11ac as "Wi-Fi 5," and 802.11ax as "Wi-Fi 6." We hope the new terminology will help simplify explanations.

The first 802.11ax/Wi-Fi 6 routers are available right now. Much as with the current MU-MIMO situation, many of that Wi-Fi version's best features won't work properly unless all (or at least most) of the devices within range of the router also support 802.11ax. Support for 802.11ax in most computers, phones, tablets, and smart devices is still rare and will probably stay that way for another year or two—so if you're in need of a router, go ahead and buy one of our current picks now instead of trying to hold out for 802.11ax.

How we picked

We researched dual- and tri-band routers from each of the major router manufacturers, including Asus, D-Link, Linksys, Netgear, and TP-Link. We also looked for routers from less well-known manufacturers with strong reviews from tech reviewers or potentially interesting features that set them apart.

We considered six criteria:

Price: You can buy a great router for $150 to $200, and a good one for $80 to $100. Routers priced higher usually add features that aren't necessary for most homes, such as gaming enhancements, extra Ethernet ports, or 802.11ax support (which most devices can't use yet). Once you pass $200, especially if you have dead spots in your home's current Wi-Fi network, you should consider a mesh-networking kit instead.

Good throughput: You need this on both the 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz bands. If you have a connection, it should be fast enough to download files quickly and stream videos smoothly.

Good range: This also applies to both the 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz bands. You should be able to connect to a well-placed router from anywhere in an apartment or a small house.

Band steering: This feature helps you make use of all available bands. All 802.11ac routers come with at least two wireless radios, and the router should be able to use all of them without requiring you to manually connect your devices to separate networks.

A fast processor: A router with a speedy processor can handle more connected devices and offer improved performance. No matter how good your radios are, the slow single-core processors found in most cheap routers can still drag things down.

RAM: Along with a good multi-core processor, 512 MB RAM helps the router deal with multiple clients simultaneously. For budget routers, which typically need to handle fewer devices, 256 MB or even 128 MB is still fine.

Most routers also offer some other features such as VPN connections, USB ports to share printers or external drives, and limited parental filtering. We looked at those, but we didn't make them the main focus of our testing—we were more concerned about the quality of the Internet access a router provided, because that's what most people will notice day to day. MU-MIMO is nice for future-proofing but by no means essential. An extra 5 GHz radio (tri-band) is good for people with lots of devices.

In addition, we used customer reviews on Amazon and Newegg, plus professional router reviews and performance rankings from CNET, Dong Knows Tech, PCMag, PCWorld, SmallNetBuilder, and Trusted Reviews, to generate our list of contenders. After identifying everything that met all of our criteria, we thoroughly tested the most promising routers ourselves.

How we tested

Testing for most Wi-Fi router reviews consists mostly of connecting a single device to Wi-Fi at various distances, trying to get the biggest throughput number possible, and declaring the router with the biggest number and the best range the winner, at least in terms of raw performance. The problem with this method is that it assumes that a big number for one device divides evenly into bigger numbers for all devices. This is usually a valid assumption for wired networking, but it doesn't work well for Wi-Fi.

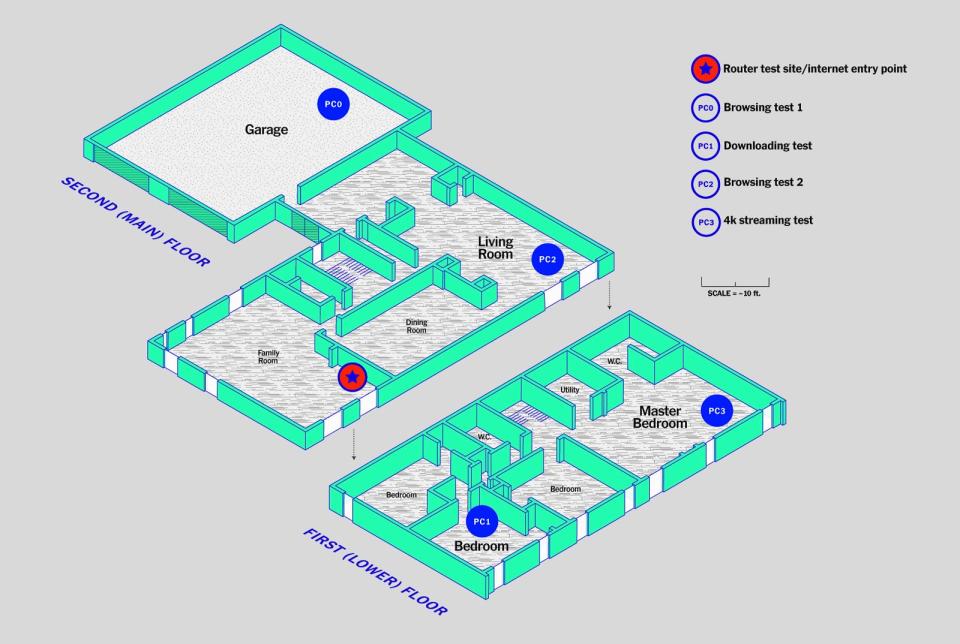

Instead of testing for the maximum throughput from a single laptop, we used four laptops, spaced around 2,300 square feet of a two-story suburban home, to simulate the real-world activity of a busy home network. Because these tests simulated real-world traffic, they did a better job of modeling real-world performance compared with a tool like iPerf, an artificial testing tool that moves data from one machine to another as fast as possible.

Our four laptops ran the following tests:

One sat in the downstairs master bedroom and simulated a 4K video streaming session. It tried to download data at up to 30 Mbps, but we were satisfied if it could average 25 Mbps or better, which is what Netflix recommends for 4K.

The second sat in the garage and simulated a Web-browsing session. Once every 20 seconds or so, it downloaded sixteen 128 KB files simultaneously to simulate loading a modern Web page; ideally pages should load in less than 750 milliseconds.

The third laptop sat in the living room across the house, simulating a second browsing session. It also downloaded sixteen 128 KB files simultaneously, and on this machine we looked for the same quick load times.

The last laptop sat in a spare bedroom downstairs at close range and downloaded a very large file. We didn't care about latency—the amount of time between when the computer made a request and when the router responded to it—for our large file download, but we did want to see an overall throughput of 100 Mbps or better.

We ran all these tests at the same time for a full five minutes to simulate a realistic extra-busy time on a home network. Although your network probably isn't always that busy, it is that busy often enough—and those busy times are when you're most likely to get annoyed, so they're what we were modeling in our tests.

These tests simultaneously evaluated range, throughput, and the router's ability to multitask. We also made sure to enable each router's load-balancing band-steering feature, when applicable, to make sure that the routers would properly distribute our client laptops across all available bands to improve performance. We didn't touch most of the other settings—you should be able to connect to the Wi-Fi and have it work without constantly fiddling with things.

To test the router's best possible speeds at close range, we placed one of our test laptops approximately 15 feet from the router, with one interior wall (or ceiling) between router and laptop; we also performed a long-distance maximum-throughput test at about 50 feet, with four interior and two exterior walls in the way. We tested throughput using a real HTTP download, the same protocol you use to view websites and download files, to better expose differences in CPU speed and general routing performance.

We used a mix of MU-MIMO–compatible and older 802.11ac USB Wi-Fi adapters to simulate a home network serving different clients. For example, many recent Mac and Windows laptops as well as top-of-the-line phones such as the iPhone XS and Samsung Galaxy S10 have MU-MIMO-compliant wireless adapters, while budget smartphones or smart speakers are unlikely to support MU-MIMO.

Because we were testing in the real world, external variables (competing signals, walls, network traffic) affected our results, just as they're likely to affect yours. The purpose of our testing was not to choose a router that was slightly faster than another; it was to see which routers could deliver consistently strong performance without major issues in real-world conditions.

Our pick: TP-Link Archer A20

The TP-Link Archer A20 is our pick because it was the fastest router we tested with the best range, it's reasonably priced, and it has features that others lack, such as a quad-core processor and tri-band radios. Those features improve performance by helping the router handle more connections simultaneously, with results that definitely came through in our tests. The TP-Link Archer A20 falls under the $200 sweet spot for standalone routers. Although routers certainly can cost more, we think those models' extra features (such as optimizations for gaming PCs and 802.11ax compatibility) aren't worth the extra cash for most folks.

The Archer A20 is a tri-band router, which means it offers two 5 GHz channels for speedy communication at shorter ranges and one 2.4 GHz channel for slower connections at longer range; most routers in this price range offer only one 5 GHz band. The Archer A20 also has a 1.8 GHz Broadcom quad-core processor and 512 MB of RAM to help it deal with the traffic from all your devices. Budget routers like the TP-Link Archer A7 make do with a single-core processor and 128 MB; those specs are certainly sufficient for handling a half-dozen devices in a small apartment, but you need the extra power of a model like the Archer A20 to maintain more simultaneous connections without getting bogged down.

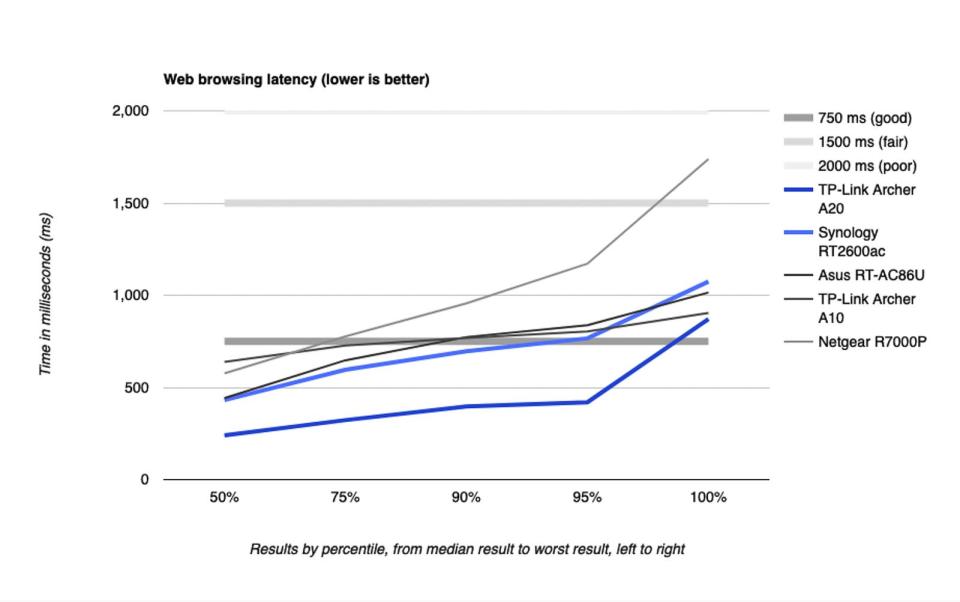

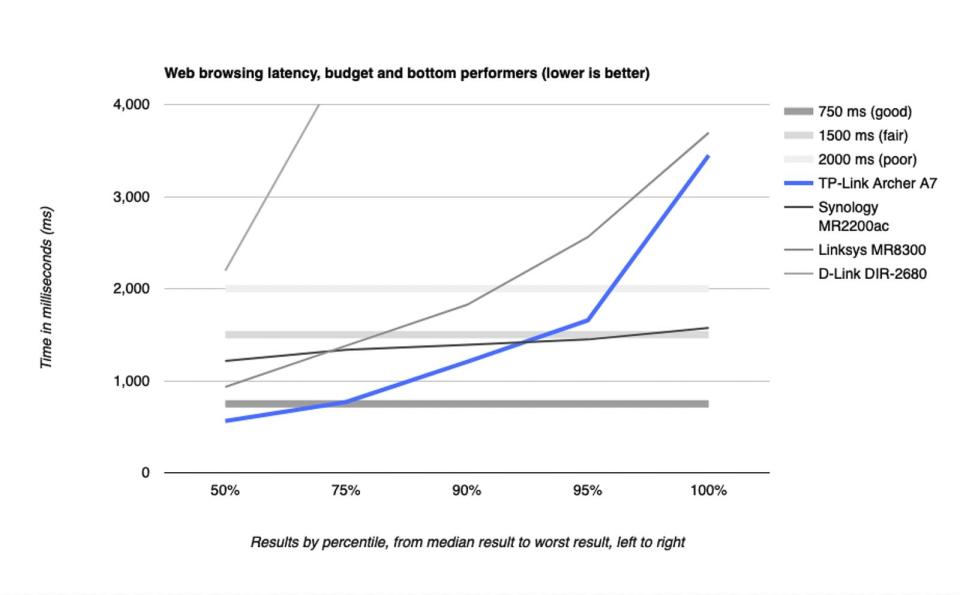

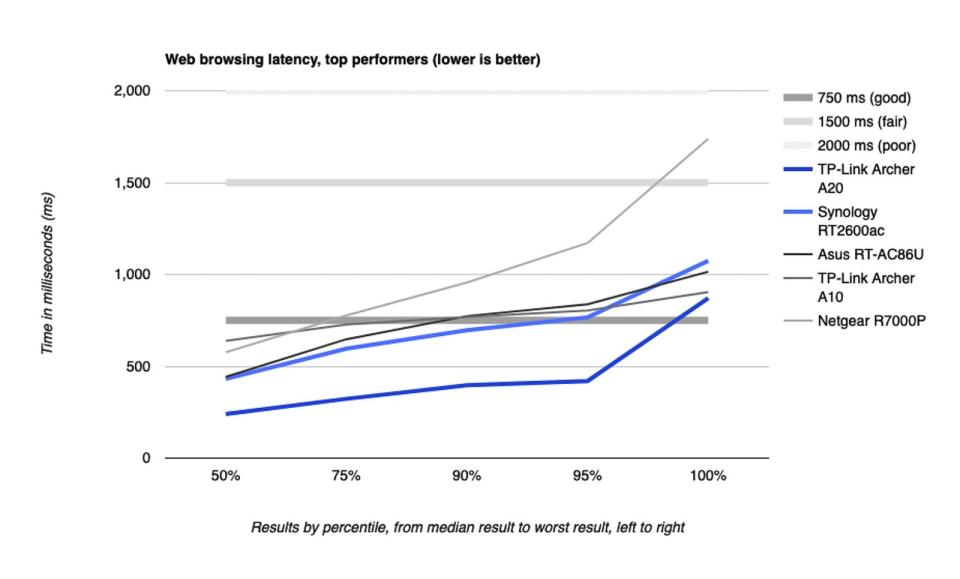

We'll get into this topic more in the testing section below, but the Archer A20 was the top performer in our multi-client test, which measures how a browsing session is affected by other devices downloading files or streaming videos simultaneously. The Archer A20's quad-core processor, its 512 MB of RAM, its second 5 GHz wireless band, and its Smart Connect band-steering feature helped it cope with all of our network traffic. We left the router's configuration as close to out-of-the-box as we could, though we had to enable Smart Connect manually. This chart shows how long our test laptop took to simulate loading a Web page while three other laptops around the house were busy doing other things like downloading files or streaming video.

This test measured how long it took to fetch a Web page, with the X-axis of the chart noting what percentage of requests were fulfilled in that amount of time. A value of 1,000 ms at 50 percent means that half of all requests had one second or less of latency. As you can see, the Archer A20 remained far under the 750 ms threshold throughout our test sequence, just breaking the line only at the 100th percentile. You likely wouldn't perceive any browsing slowdowns, even while the other clients were hammering the router with streaming, downloading, and other browsing requests. Out of the 10 routers we tested for this guide, the Archer A20 was the fastest and most consistent.

The Archer A20's band steering was able to keep all our laptops connected to the two 5 GHz bands without slowdowns, even for our long-range clients in the garage and master bedroom. That's good, because it frees the 2.4 GHz channel for other devices that don't have 5 GHz radios.

The Archer A20 looks like a box with a set of six antennas that swing up out of the router's body (we tested it with the antennas deployed). It has the usual set of four Gigabit Ethernet ports on the back, along with a single marked WAN port that you connect to your cable modem or fiber gateway. It has one USB 2.0 port and one USB 3.0 port on the back so you can connect a USB hard drive or SSD for media streaming or file sharing. The router can also act as a Time Machine backup device with external storage.

A feature called link aggregation (aka port bonding) lets you achieve Internet speeds up to 2 gigabits by using two connections at the same time. You can connect the main WAN port and LAN port 1 on the back of the router to a cable modem that also supports link aggregation, such as our upgrade pick, the Motorola MB8600. Although very few ISPs support faster-than-gigabit Internet now, this feature offers a way to future-proof if you know that such speeds are something you're interested in (though most people don't need a connection that fast). You can also link two of the Archer A20's LAN ports together to increase bandwidth for networked storage devices that support link aggregation, such as the Synology DiskStation DS418play. Both situations make more sense if you're running a business from your home.

The TP-Link Archer A20 comes with a two-year warranty, double the length of the protection that comes with the Netgear R7000P, our previous top pick. Routers usually come with one to three years of coverage, though most manufacturers give you two years.

Flaws but not dealbreakers

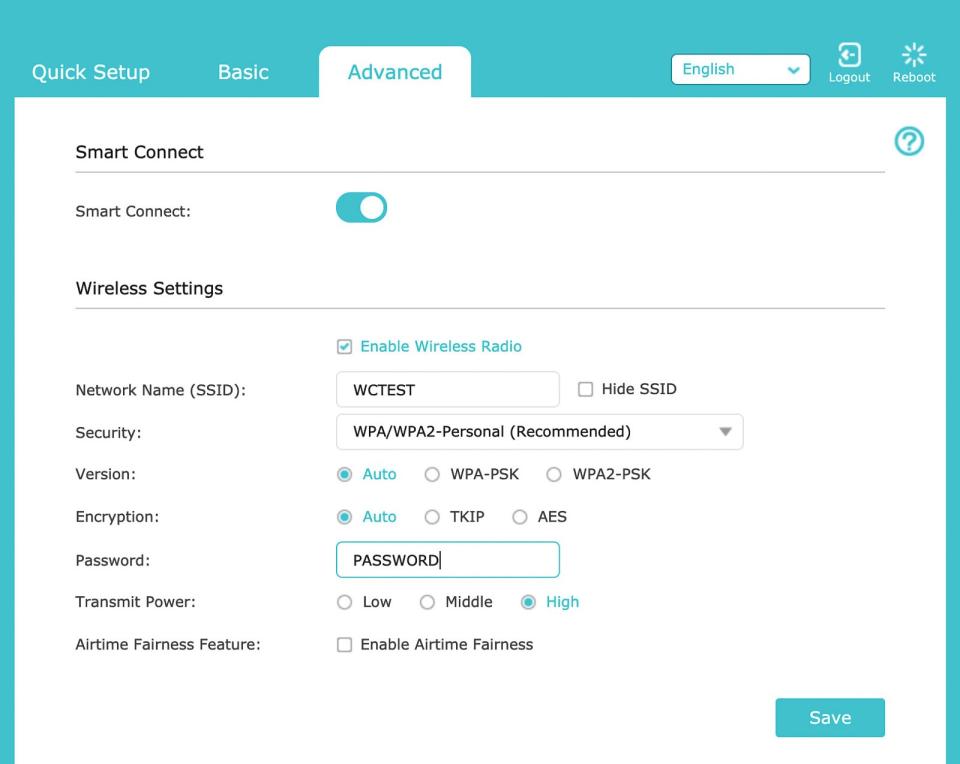

When you first set up the Archer A20, its Smart Connect band-steering feature is off by default, and the router gives you three discrete (one 2.4 GHz and two 5 GHz) wireless networks instead. It's a quick fix—you simply have to switch Smart Connect on at the Wireless Settings admin screen to merge the SSIDs and networks—but it's an extra step that is easy to miss.

Although the router isn't very tall (1.5 inches with the antennas stowed), the base is an 8-by-8-inch square, which could be an issue if you are replacing a taller router that didn't take up so much horizontal desk space. For example, the Synology MR2200ac is a relatively svelte 6 by 7.7 by 2.6 inches (HWD), and the now-discontinued Apple AirPort Extreme was even slimmer at 6.6 by 3.9 by 3.9 inches (HWD).

We recommend installing a whole-home mesh kit if you're replacing a router and extenders in a larger home, but you can buy a mesh extender for the Synology RT2600ac and TP-Link Archer A7 if you need more coverage (though we haven't tested those to see how they stack up to actual mesh kits yet). The Archer A20 isn't compatible with mesh extenders yet, but TP-Link is planning to add OneMesh compatibility in a firmware update. That delay shouldn't be a problem unless you know you'll need a mesh network from day one—and in that case we recommend you buy a mesh-networking kit outright.

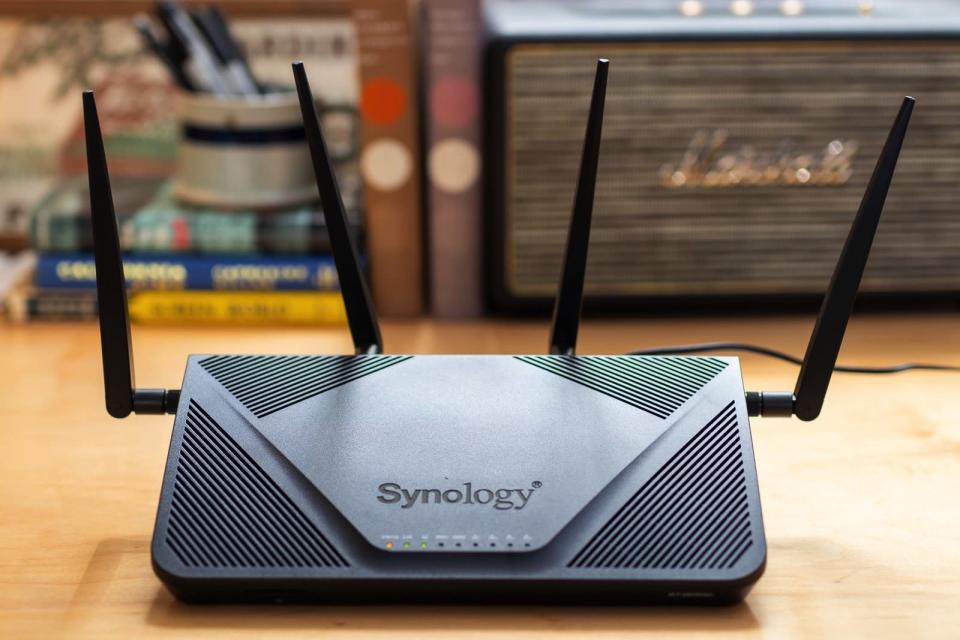

Runner-up: Synology RT2600ac

The Synology RT2600ac router is easy to set up and extremely configurable. It was also speedy on our throughput tests, and it offered excellent performance when serving multiple clients. It's typically more expensive than the Archer A20, and because it lacks a second 5 GHz radio, it may reach its limits earlier if your household owns a lot of wireless devices or if the 2.4 GHz band in your area is congested, but it still performed well on our tests. You may not be familiar with Synology, but the RT2600ac has been available for a couple of years, and it builds upon the company's expertise with network-attached storage units and other network devices. The RT2600ac has received good reviews from sites such as Dong Knows Tech, CNET, PCMag, and SmallNetBuilder.

This Synology router ended up alongside two other dual-band routers (the Asus Blue Cave and Asus RT-AC86U) at the top of our performance charts. Like the Archer A20, each of these routers was able to handle the traffic our multi-client test generated and to give us a smooth browsing experience. And the Synology was able to keep a strong connection to our long-distance testing site, transferring data at a speedy 166 Mbps throughput (by comparison, the budget TP-Link Archer A7 was able to manage throughput of only 27 Mbps to the garage).

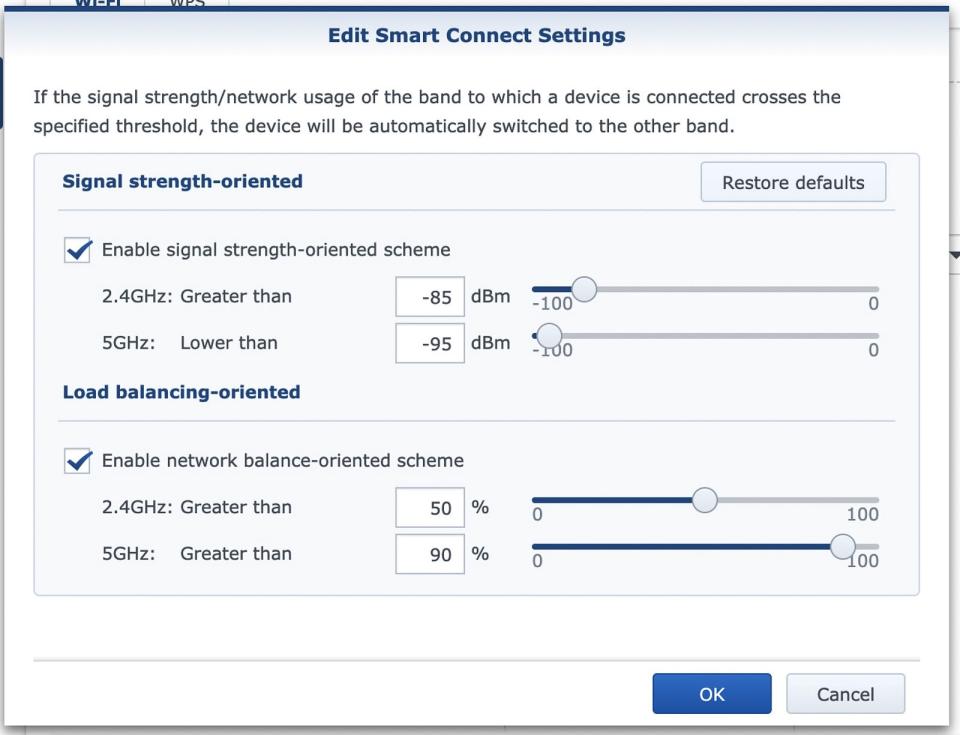

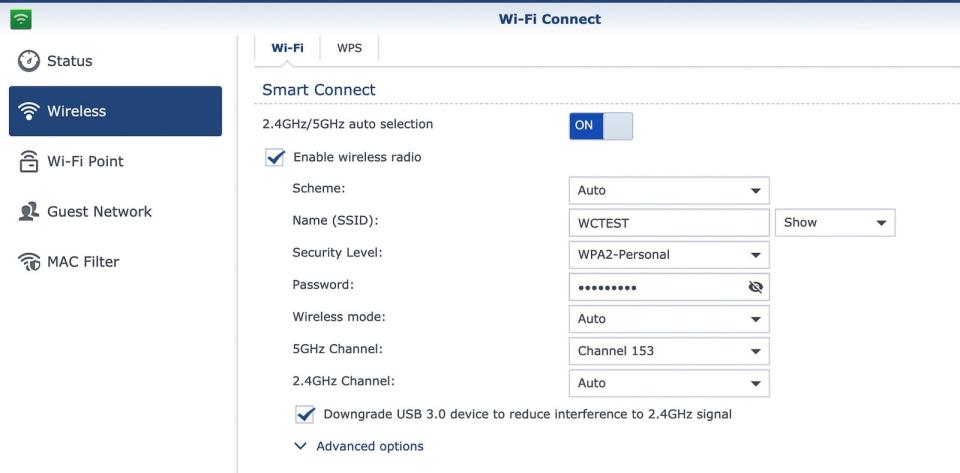

Smart Connect (aka band steering) worked out of the box, so we didn't have to search the administration interface to enable it as we did on the TP-Link routers. It chose bands intelligently, shifting the two farthest laptops (in the master bedroom and in the garage) to the 2.4 GHz band automatically during our multi-client tests. When we ran our single-client maximum-throughput test, the client in the garage automatically jumped back onto the 5 GHz channel. If you're tech savvy, you can tweak the Smart Connect thresholds to determine exactly when clients will connect to the 2.4 GHz or 5 GHz channel, but we didn't need to do that to get good performance during this round of testing.

The RT2600ac comes with a 1.7 GHz Qualcomm dual-core processor and 512 MB of RAM. That's two fewer cores than in the Archer A20's CPU, but a dual-band router can't deal with as many clients overall, so the dual-core CPU is fine.

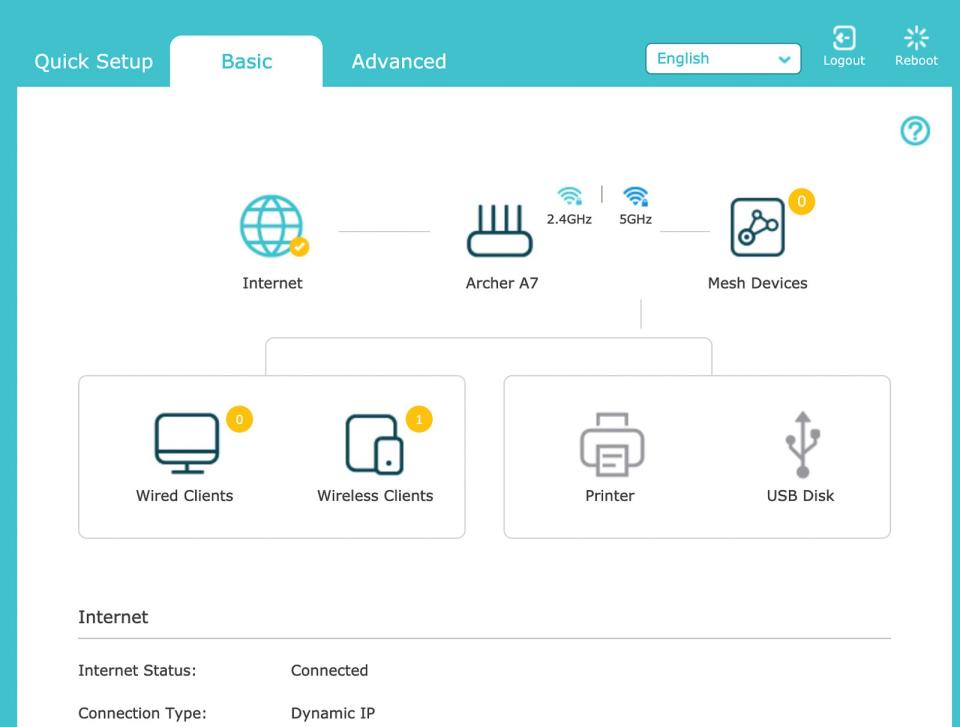

We found setup quick and easy using Synology's SRM (Synology router management) operating system, which is based on the company's operating system for NAS boxes. The TP-Link Archer A20's setup was similar to that of other routers we've configured in the past: The process is straightforward when the setup wizard is guiding you, but you can easily get confused when trying to find a specific setting after that initial setup. In contrast, Synology's SRM looks and reacts like a Windows-based operating system, so you'll find settings grouped logically. If you have our pick for the best NAS for home users, the Synology DiskStation DS218+, you're probably familiar with the interface. It runs in a browser tab, and it gives you windowed panes to navigate between settings.

The interface gives each function its own window, which helped us focus on the task we needed to do. Once we got used to the interface, it made more sense to look for various wireless-channel settings in the Wi-Fi Connect control panel. Compare that experience with the TP-Link interface, where you have to remember that the SSID and password are available under the Wireless Settings section in the Basic settings pane but that the security level is two levels deep (under Advanced Setup, and then Wireless Settings) in the Advanced settings pane. The windows also let you keep comparable info open at the same time, so you can check how a setting change affects your clients' connections without having to slog back through more tabs and menus.

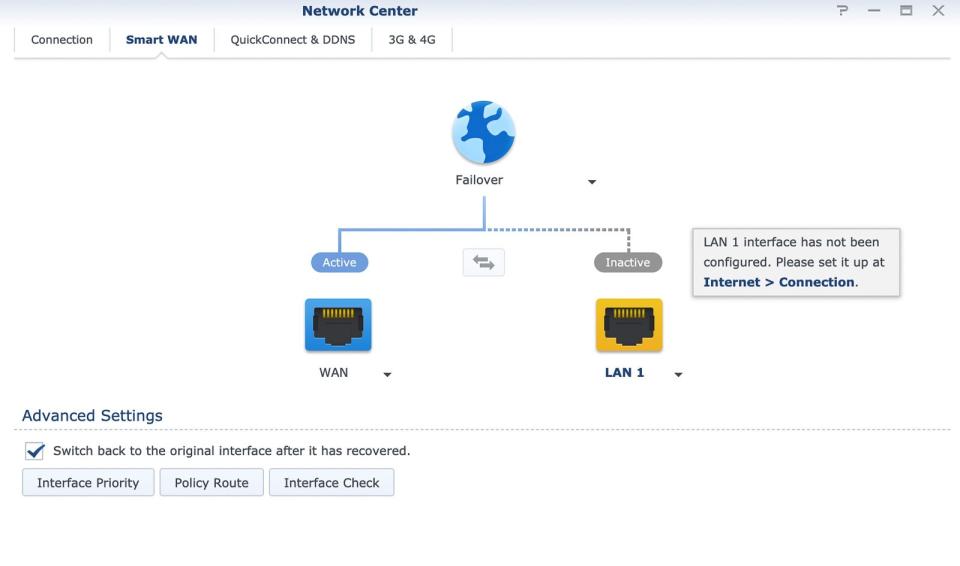

Other advanced features include easy-to-set-up dual WAN failover protection. That is, if your main ISP connection goes down, you can plug your smartphone or a USB 4G modem into the router, and it will use the mobile Internet connection as a backup. Or you can connect a second cable modem or DSL line to LAN port 1, and if the main Internet connection goes down, the router will automatically switch to the backup (and back again to the main line once it's up).

The RT2600ac can act as a base station for one or more Synology MR2200ac routers acting as wired or wireless mesh extenders. Although these can extend an existing network to underserved parts of your house after you purchase a standalone router, we still recommend buying a tri-band mesh router kit if you know you will need to cover a large area or have indoor obstacles that block Wi-Fi, such as masonry.

Like the TP-Link routers, the Synology RT2600ac comes with a two-year warranty.

Budget pick: TP-Link Archer A7

The TP-Link Archer A7 prompted us to reverse our past theory that you have to forgo vital features to find a router for under $100. While the top picks in this guide outperformed the Archer A7 overall, tested alongside our contenders the Archer A7 held its own and surpassed several routers costing double the price or more.

A recent firmware upgrade added band steering (Smart Connect) to the Archer A7, along with OneMesh support. The latter will extend your network with the help of add-on routers or mesh Wi-Fi extenders, but Smart Connect is the more significant upgrade since it will automatically assign devices to the 2.4 GHz or 5 GHz wireless band based on which one will deliver better performance. We don't think the A7 would be as robust as the tri-band Archer A20 for a larger home with dozens of devices—it has one fewer wireless radio, less RAM, and a weaker processor—but this router is certainly sufficient for a starter home or an apartment with fewer smartphones and PCs.

The Archer A7 has a 750 MHz single-core Qualcomm processor and 128 MB of RAM, which fall pretty far short of the quad-core processor and 512 MB of RAM in the Archer A20, but its performance in our tests certainly showed that it is a capable router.

During our testing, the Archer A7 connected the long-range client in the garage on the 2.4 GHz channel while retaining the others on the 5 GHz channel, economically splitting the load so that the download and 4K streams didn't interfere with the two clients browsing the Web. The budget CPU and low memory showed their limitations when the measurements were in the 95th to 99th percentile. This test result is a pretty good indicator of what living with this router would be like in real life: One of every 20 or so page loads will be noticeably slower than average, in this case taking a little over one and a half seconds to three seconds. That's longer than the 0.42–second result we observed at the 95th percentile for the Archer A20—but the Archer A7 is less than half the price.

Tested throughput at close range in the spare bedroom was pretty good, and this model ran neck and neck with the Linksys MR8300 and the Synology MR2200ac. Throughput at longer range in the garage was quite a bit lower due to the 2.4 GHz connection. That said, the garage client was still able to view a 4K video stream smoothly.

The Archer A7 is compatible with TP-Link's OneMesh routers and mesh extenders. You can use the latter to quickly connect dead zones in your home. However, since it uses the same wireless radios as every other device on your network, it's not as adaptable as a mesh-networking kit that lets you use either wired backhaul or dedicated wireless radios. That said, it's notable that you even have that option in a budget router. We're planning on testing TP-Link's OneMesh alongside dedicated mesh-networking kits in our next update.

The Archer A7 also comes with a two-year warranty, on a par with the coverage for the Archer A20 and Synology RT2600ac.

An overview of the test results

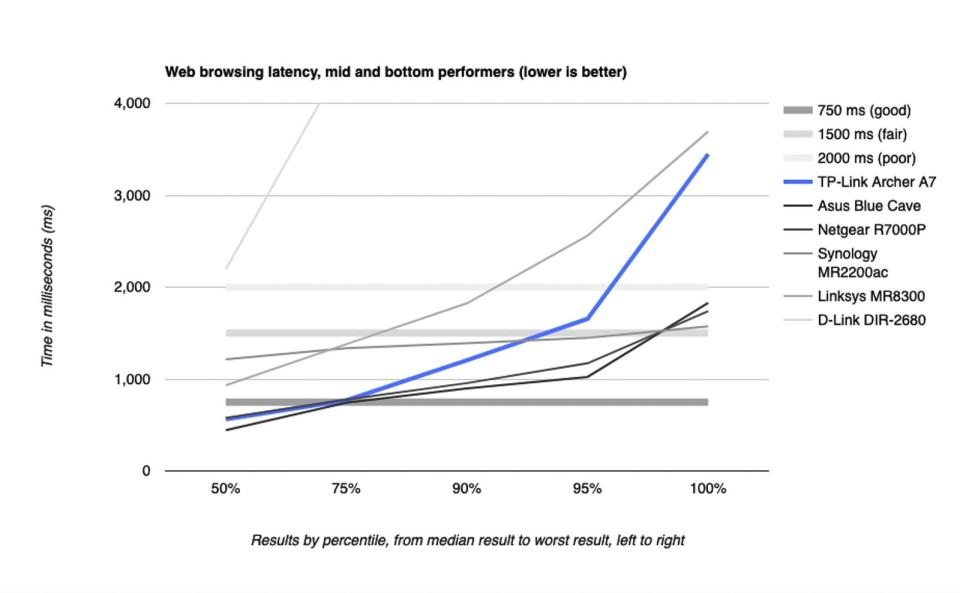

The TP-Link Archer A20 was our most robust and consistent router when we stress-tested with multiple clients simultaneously. The other top performers came very close to the Archer A20, up until the 90th to 95th percentile.

What this graph shows is how many milliseconds it took to simulate loading a Web page during our multi-client tests. On the left side of the graph is the 50th-percentile result—the result in the middle of the range. We also took a sample at the 75th, 90th, 95th, and 100th percentile—the last being the worst results we got from each device. Keep in mind that while the laptop in this test was loading Web pages, three others were (simulating) downloading a big file, streaming 4K video, and browsing a second website—this was a busy little network, at a busy time.

Although the TP-Link Archer A20 was the clear winner, the Synology RT2600ac, Asus RT-AC86U, and TP-Link Archer A10 were effectively in lockstep. They provided a smooth browsing experience up to the 95th percentile; this means one of every 20 or so page loads will be noticeably slower than average. But even then, the hiccup will last only about a second, barely enough time for you to react and start wondering if there is a problem.

The other half of the group told a different story. The Asus Blue Cave and the Netgear R7000P, our former top pick, as well as the TP-Link Archer A7, our budget pick, did all right up until the 75th percentile but showed a bit more of a spike after the 90th percentile (though still sticking under the 2,000 ms threshold, where things would really go off the rails).

Disappointing results were especially noticeable for the Linksys MR8300 and the D-Link DIR-2680: The MR8300 started off on shaky ground and rapidly moved into poor performance after the 75th percentile, while the DIR-2680 began in poor territory and just went off the charts after that. The MR8300 band-steered all four of our clients to its 5 GHz radio rather than splitting them between bands, and its single-client throughput tests (explained below) demonstrated poor performance at long distance. The Synology MR2200ac coped better on the test by shifting the browsing client to its 2.4 GHz radio, but its long-range throughput was the slowest of anything we tested—if one device on your network is struggling to communicate with the router, it can drag down the performance of everything else. The results we got from these routers illustrate why we use multi-client tests for our router guides—if you were to go by only the single-device close-range throughput numbers below, you might think the DIR-2680 was a decent performer. However, our browsing-latency test shows that in a worst-case scenario—when lots of household members are actively using your Wi-Fi at the same time—the DIR-2680 will show you a dreaded spinning pinwheel more often than the other routers here.

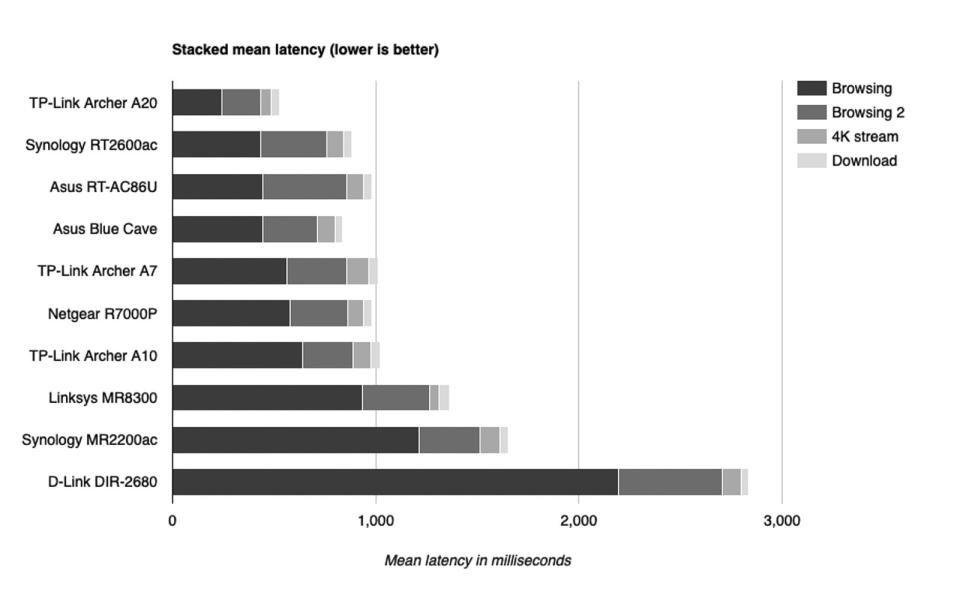

This is a stacked bar graph of the mean latency results from each of our four test clients—adding all those numbers together gives you an idea of how each router might perform when lots of devices on your network are busy. Latency measures how long it takes your inputs to reach the other end of the connection—the time between your clicking a link and the page loading. Unresponsive Web browsing is the first thing most people notice going wrong, so we've sorted our results by the length of that bar here.

The TP-Link Archer A20 was clearly the winner in this test, with the Synology RT2600ac, Asus RT-AC86U, and Asus Blue Cave stacked in a group below that. Surprisingly, the TP-Link Archer A7 came next, outpacing multiple more-expensive routers, followed by the Netgear R7000P, our pick in the previous version of this guide. Again coming in last place, the D-Link DIR-2680 labored during our multi-client tests.

We checked how each router performed at short range to the spare bedroom and at long range to the garage by beaming a large file repeatedly to our clients on their own. The majority of the routers were able to top 200 Mbps at close distances, with the best-performing routers pushing 230 Mbps. Only a couple of stragglers (the TP-Link Archer A7 and the Linksys MR8300) fell a bit behind at 180 Mbps, which is still a speedy throughput score.

At long distance, half of the routers kept our garage client on the 5 GHz channel, and the other half switched it to the slower but longer-range 2.4 GHz channel. Most but not all of the routers that switched to 5 GHz stayed above 166 Mbps, while the top three kept a 200 Mbps throughput measurement. The Linksys MR8300 stayed on 5 GHz but was able to download at only 59 Mbps. One nice thing to report is that all of our competitors were able to download at 25 Mbps or better at long range. According to Netflix, 25 Mbps is the minimum comfortable throughput threshold for 4K video.

Router setup and network maintenance

Regardless of the router you're using, you need to do a few things to maintain a secure, reliable wireless connection:

To access your router's Web-based configuration screen, don't use any domain names that your router's manufacturer may have provided as a shortcut—such domain names have been known to get hijacked and can open you up to attack. Instead, connect a desktop or laptop to the router (wired or wireless), open a Web browser, and type in the router's IP address; here's how to find it.

As soon as you set up your router, change its administrator password.

Use WPA2-PSK (AES) encryption for the best speed and security on your Wi-Fi networks. (Use your router's mixed-mode setting—AES and TKIP—only if you have older devices that don't support WPA2.) WPA3 is a newer security standard that purports to be more secure, but very few WPA3-compatible routers and devices are available so far. WPA3 is backward-compatible with WPA2, so you're fine if your router has it.

Immediately check for any available firmware updates for your router, and recheck every few months. Updating will help ensure that you get the best performance, security, and reliability. Our picks (the TP-Link Archer A20, Synology RT2600ac, and TP-Link Archer A7) will alert you to new firmware updates when you open the Web-based administration page, but you usually have to open that page regularly to check. If you're interested in some straightforward steps you can take to make your router more secure, we like this guide by SwiftOnSecurity.

Try to place your router in a central location in your home. Don't stash it next to a bunch of other electronics, and don't just shove it somewhere in the basement. Don't waste your time wiggling the antennas around—they're omnidirectional. You can't get more than a 1 or 2 dBM gain—or loss—from a different antenna position, and that isn't enough to fix any problems you might be having.

Don't just connect everything to your 5 GHz radio "because it's faster." Yes, 5 GHz is faster than 2.4 GHz—at short range, at least. But the more devices you've got crammed onto a single radio, the more problems you'll encounter. Note that tri-band routers have two 5 GHz radios. You can connect critical devices such as a streaming set-top box or a gaming PC to its own 5 GHz radio manually. If you don't have or aren't using band steering, be sure to manually connect your devices to all the bands your router offers.

To optimize your network, grab an app such as Wi-Fi Analytics (PC/Android), WiFiAnalyzer (Android, open source) or WiFi Explorer (Mac) to make sure you've configured your Wi-Fi networks correctly. See whether competing wireless networks are present on channels 1, 6, and 11 on the 2.4 GHz band, or if any other Wi-Fi networks are on the 5 GHz band. If you're having frequent problems with lots of signal bars but slow speeds, try changing to a different Wi-Fi channel—but don't get too hung up on which channel seems to have the most networks visible. Active Wi-Fi use is what causes congestion: One neighbor network with kids home and playing all day might give you more trouble than three neighbor networks with little or no activity.

If your laptop is having issues connecting to your router, make sure that you have the latest drivers for your laptop's Wi-Fi card. You can usually find these on your laptop manufacturer's website, but the Wi-Fi card's manufacturer might have more-recent drivers. We encountered this issue once during our previous testing: One of our laptops, an Acer, would connect to a router's wireless-ac network but drop the speeds to almost nothing. When we updated our Acer laptop with Wi-Fi drivers straight from Intel, which were newer than the ones Acer offered, our problem went away.

What to look forward to

Netgear has introduced a new gaming router, the Nighthawk Pro Gaming XR300, which is available for $200. It's an 802.11ac router with four Gigabit Ethernet ports, a dual-core 1 GHz processor, and dual-band Wi-Fi. We skipped it this go-around because it doesn't yet support band steering (Smart Connect). We'll likely test it in our next update once that issue has been resolved.

Netgear also released a new 802.11ax router, the Nighthawk AX4 RAX40. It's a dual-band router with four Ethernet ports and an 800 MHz Intel dual-core processor. It's priced around $200, and like the XR300 it doesn't support band steering right now—when (and if) it does, we'll take a look.

D-Link released a set of 802.11ac Exo-branded routers and Wi-Fi mesh extenders at the CES 2019 trade show. They weren't available during our test period for this guide, but we'll look out for them for our next standalone Wi-Fi router and Wi-Fi extender guide updates.

THE COMPETITION

Our previous pick: Netgear R7000P Nighthawk

The Netgear R7000P Nighthawk was our pick during the last iteration of this guide, but its ranking has dropped a few notches. Its performance put it in the middle of the pack compared with the new routers we tested, and it has a shorter (one-year) warranty. The Archer A20's price is usually $10 to $20 higher than that of the R7000P, but we'd pick the Archer A20 for its extra performance, two-year warranty, and future-proofing features like link aggregation.

Everything else

TP-Link sells a variant of the Archer A20 called the Archer C4000. The company confirmed to us that the hardware was "almost identical" but that "the available firmware features on each model may vary." Most people should stick with the Archer A20, since we haven't tested the C4000.

The Asus RT-AC86U and TP-Link Archer A10 were notable competitors; they matched the Synology RT2600ac in performance so closely that you'd have to take a magnifying glass to the graphs of their results to see the difference. All three trailed the Archer A20 in speed and tri-band support, but we enjoyed the RT2600ac's ease of use, its admin interface, and its advanced features, such as the ability to tweak its band steering; these factors pushed the RT2600ac ahead of both the RT-AC86U and Archer A10.

The Asus Blue Cave showed promise because of its design, AiMesh compatibility, and good reviews. It performed just as well as the Netgear R7000P and TP-Link Archer A7, landing in the middle of the pack, but it didn't distinguish itself beyond its easy-to-live-with exterior and middling price.

You can configure the Synology MR2200ac as a standalone router, but this model is more notable because you can use it as a mesh extender along with the RT2600ac. The MR2200ac has only one Ethernet port, though you can use it to extend a wired network. It uses the same excellent Synology SRM router OS as the RT2600ac, too. However, it finished in the bottom tier of our performance tests. We're definitely going to look at the MR2200ac again when we update our mesh-networking and Wi-Fi extender guides, but we suggest skipping it as a standalone router.

The Linksys MR8300 and D-Link DIR-2680 wound up at the bottom of our performance charts. Both suffered lower throughput in our long-range tests, and both were less able to handle the browsing traffic when all four of our clients were tagging the router at the same time. The MR8300 is notable for being compatible with Linksys's Velop mesh system and for using a mobile app as its primary interface. The DIR-2680 has internal antennas, which make it look less like a robot, and it includes McAfee-branded Internet security, but ultimately it trailed the other models here on our tests.

We considered routers from Motorola, specifically the MR1900, MR1700, and MR2600. The MR1900 will be discontinued soon, while the latter two routers lack band steering and are both more expensive than the TP-Link Archer A7.

We also thought about the TP-Link Archer A5 and Archer A6, since both rank among the least expensive 802.11ac routers with a typical price tag under $50. However, both also lack band steering, which is available in enough inexpensive routers now that we consider the feature to be a must-have.

Previously tested

We tested 14 standalone wireless routers for previous iterations of our guide. Most of these routers are still available, though some have been replaced by newer models; we didn't retest these routers in 2019, but we stand by our dismissals.

The TP-Link Archer C7 was our main pick for several years due to a combination of an extremely low price, a long range, and high throughput. Our new budget pick, the Archer A7, is the continuation of the C7 line under a new name. The C7 does a good job within its limitations, but more modern routers outperform it, particularly if you don't want to manage multiple network names.

The Asus RT-AC3200 is a tri-band router at a flagship dual-band router price, with great range and coverage plus really good device- and traffic-analysis capabilities in its UI. Unfortunately, its band steering was broken when we first tested it, and it's still broken; it claims to steer across all three bands, but in our testing it never once connected a device on 2.4 GHz.

Netgear's R7800 is an older model that doesn't support band steering.

TP-Link's Archer C5400 is a tri-band router offering MU-MIMO support and 4×4 radios. Unfortunately, what it doesn't offer is band steering, which makes those three radios inconvenient to use. The C5400 also had lackluster long-range 5 GHz performance in our tests.

Netgear's R6700 was updated to the R6700v2 in early 2017, but it's not the upgrade you might expect. The revised version has a MIPS CPU instead of the older model's more-powerful ARM processor, and the R6700v2's MediaTek radios are tweaky and unreliable.

Apple officially discontinued the AirPort Extreme in spring 2018. When this device was current, it was a decent but not great home router; now that it's unsupported, we don't think it's worth buying at any price.

The Amped Wireless Titan offers really good short-range 5 GHz performance. However, in our tests its longer-range 5 GHz performance was quite poor, and its 2.4 GHz performance was mediocre; it also lacks band steering.

Linksys's EA8300 is a tri-band router with band steering. When we tested the EA8300 in 2017, its version of band steering crammed all of our devices onto the first 5 GHz radio, as though the router had no band steering at all.

The Securifi Almond+ was easy to set up from its built-in touchscreen. Unfortunately, the Wi-Fi performance from the Almond+ was mediocre at best and particularly underwhelming at long range.

The TP-Link Archer C9 performed poorly on our tests. The C9 also suffers from a weird, awkward standing-on-end design, and TP-Link sells five separate hardware revisions, making it hard to tell what you're going to get (or how long the company will support it, if you buy one).

We thought the D-Link DIR-878 dual-band router showed potential with MU-MIMO support, band steering, and beamforming. Like the Netgear R6700v2, however, it uses MediaTek radios, and so far we haven't seen anything with a MediaTek Wi-Fi chipset that performs reliably.

D-Link's DIR-867 is a lower-cost version of the DIR-878. Under the hood, it uses the exact same CPU and Wi-Fi chipsets as its larger counterpart, but—oddly—it tends to perform slightly better. "Better" isn't the same thing as "well," though, and we cannot recommend either router.

The Ignition Labs Portal makes bold claims about performing leaps and bounds better than competing routers by making use of restricted DFS frequencies. The theory is, if your environment is swamped with lots of devices, using other frequencies will bypass congestion and make your experience better. Unfortunately, those frequencies are restricted for a reason: They're used by military radar, air-traffic controllers, and similar high-priority devices. Even though it's legal to use those frequencies in civilian devices, you have to respect those "big boy" devices' priority and cease transmission entirely if you can sniff even a hint of them in operation. This limitation led to very poor results for the Portal in our testing.

The less said about D-Link's DIR-842, the better. The DIR-842 was completely unable to connect to our test clients at long range. Its throughput was also poor at our short-range test site.

Jim Salter contributed to previous versions of this article.

This guide may have been updated by Wirecutter. To see the current recommendation, please go here.

When readers choose to buy Wirecutter's independently chosen editorial picks, Wirecutter and Engadget may earn affiliate commissions.