Local governments are still woefully unprepared to fight ransomware

And that's making would-be attackers even more brazen.

Our state and local governments found themselves under siege in 2019 from William Plunketts for the internet age. But rather than pistols and roadblocks, this new generation of bandits come armed with encryption algorithms and demands for bitcoin. Can today's American cities and counties, long hamstrung by both a lack of interest and funding for cybersecurity efforts ever hope to withstand these digital muggings? Just ask Lake City, Florida.

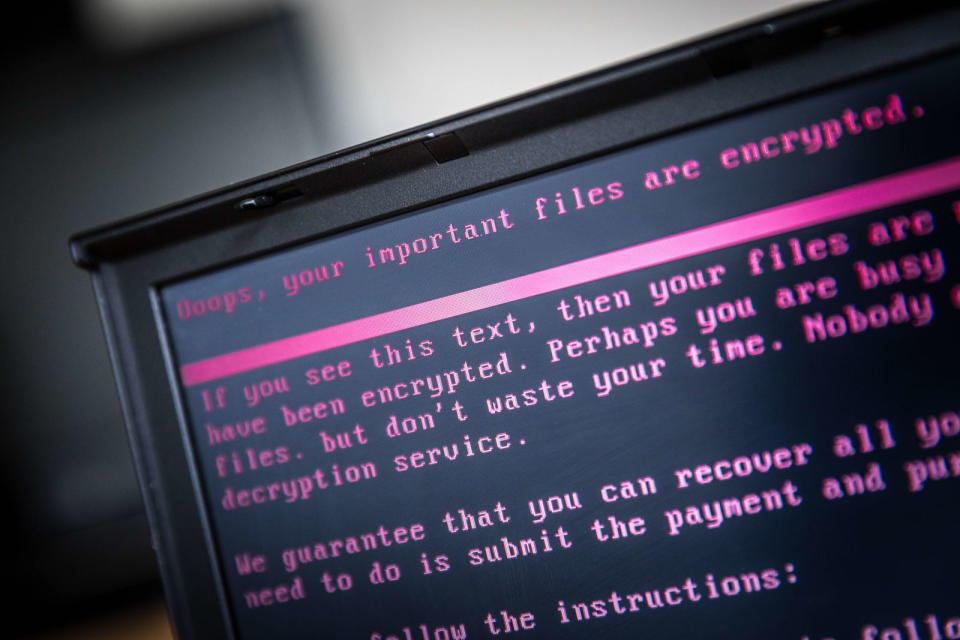

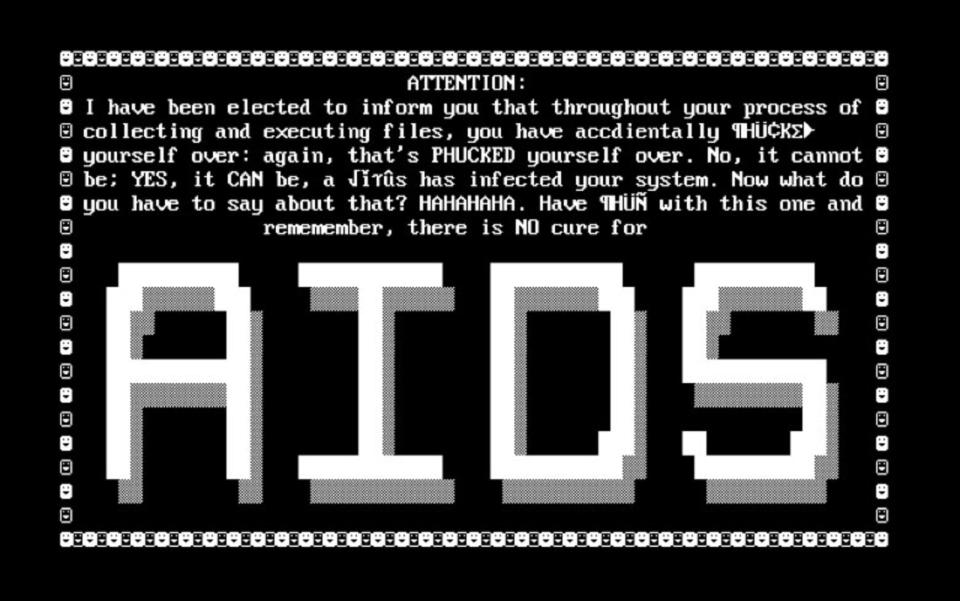

A string of high-profile attacks over the past six years have brought the threat of encountering ransomware to the forefront of public consciousness. However, the practice of remotely encrypting data and holding it for ransom is nearly 30 years old. 1989's PC Cyborg virus, colloquially dubbed the AIDS Trojan as it initially targeted AIDS researchers, marks the first known such attack.

AIDS Trojan was designed by biologist, Joseph Popp, distributing 20,000 infected disks at the World Health Organization's AIDS conference that year. Once loaded onto an unsuspecting PC, the program would hide all directories and encrypt all files on the C drive. The only way, initially, to unlock the computer involved mailing a check for $189 to a PO Box in Panama. Luckily, Popp utilized an easily broken cryptography scheme and tools were quickly developed to counter the Trojans effects without having to pony up cash.

For the next nearly three decades ransomware attacks faded into the background of computer technology. If there were any such extortion cases, they were not large or heinous enough to warrant much attention from the computer security community or the media. That changed in 2013 with the release of CryptoLocker and its variants. That year, the program targeted the Swansea Police Department in Massachusetts via a malicious email attachment, locking down the department's computer file system until the police relented and paid a $750 ransom fee. How quaint.

The problem has only gotten worse in the six years since. A study complied by Recorded Future and published this May scoured local news sources and found 169 instances of ransomware attempts against state and local governments since the Swansea attack. That's roughly 45 a year on average between 2016 and 2018, with the number spiking last year with 53. Hackers have launched another 21 reported ransomware attacks in the first half of this year alone, though those numbers may be higher given that the FBI relies on ransomware targets to self-report their attacks.

"Overall trends show a drop in volume for the year, but an increase in focused, sophisticated attacks aimed at businesses," the 2019 Malwarebytes' State of Malware report found. "Indeed, the only real spike in numbers has been in the realm of the workplace, with a distinct lack of interest and innovation aimed at consumers."

These attacks aren't particularly effective and the likelihood of receiving payment from a target varies widely, which is part of the reason that perpetrators have stopped fiddling around with individual marks and largely moved onto bigger prey like hospitals, universities, and government agencies.

A 2019 report from CyberEdge found that only 45 percent of organizations hit with ransomware paid the fee, though 17 percent of those who paid lost their data anyway. The corollary to that is 19 percent of firms who refused to pay were unable to recover their data via alternative methods, so you're nearly equally screwed whether you pay up or not. The numbers are even worse if government agencies are targeted. Recorded Future's study found that only 17 percent of afflicted agencies actually paid the ransom while a full 70 percent told the hackers to go kick rocks and decrypted the data themselves.

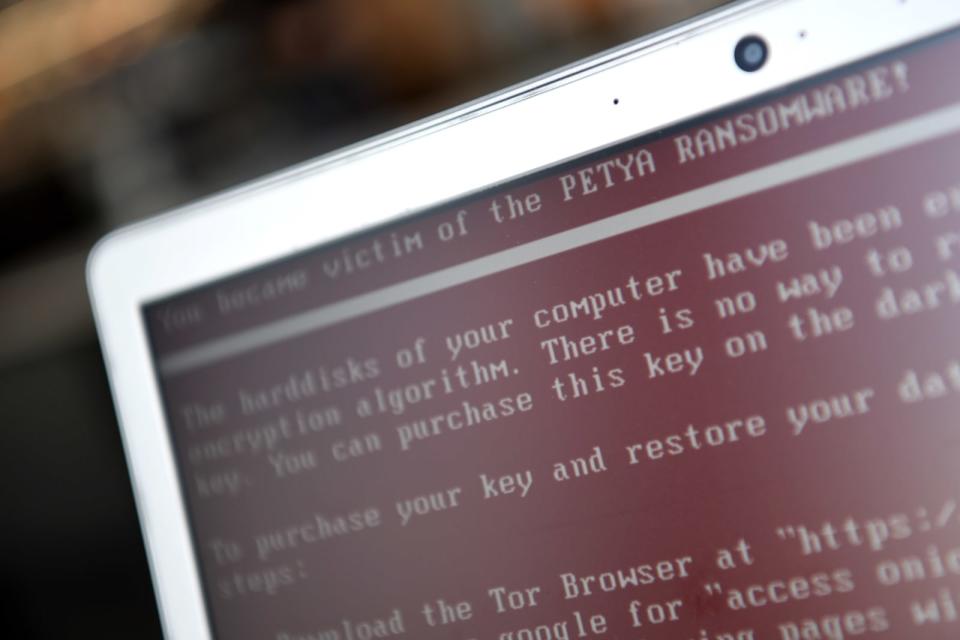

But when the government does pay, it pays through the nose. In late June, the town council of Lake City, Florida -- population 65,000 -- agreed to shell out 42 bitcoins, valued at nearly half a million dollars, in order to regain access to their administrative network. The city had been shut out of their systems for nearly two weeks after suffering a massive "triple threat" malware attack earlier that month. Compared to Rivera City, Florida, Lake City got off light. Rivera's leadership had to hand over 65 bitcoins worth an estimated $600,000 a few weeks before -- and that's after they'd already agreed to spend nearly a million more dollars to rebuild their digital infrastructure from the ground up. These follow a $400,000 attack against Jackson County, GA in March, a strike against Albany, NY that same month, and an attack against the parking meter system in Lynn, MA in May. Heck, Johannesburg, South Africa suffered a malware attack against its electrical grid just this morning.

"We were crippled, essentially, for a whole day," Gregory McGee, vice president of the Albany Police Department's union, told CNN.

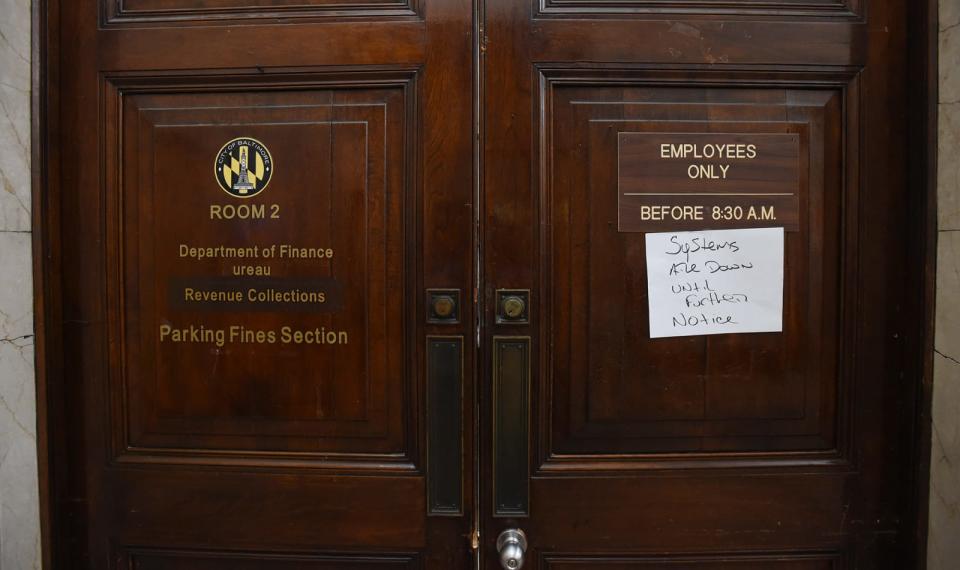

Baltimore, Maryland has been especially hard hit. The city's 911 and 311 systems were knocked offline in 2018 due to a ransomware attack, then a majority of the city's servers were infected this May. Luckily, none of the city's essential services were disrupted. The group behind the heist demanded 3 bitcoin (around $17,500) per server unlock or, generously, they'd take 13 bitcoin (a little over $76,000) to decrypt everything. The city refused to pay the ransom and has since set about restoring its impacted systems, albeit at an extravagant cost. The city estimates that it will require $18.2 million to undo the damage caused, including potential revenue losses. The city expects to spend at least $11 million of that total by the end of this year.

"You've got increasingly sophisticated and very persistent bad guys out there looking for any vulnerability they can find and local governments, including Baltimore, who either don't have the money or don't spend it to properly protect their assets," Don Norris, a professor emeritus at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, told the Sun at the time of the attack.

"I'm not surprised that it happened," he continued, "and I won't be surprised when it happens again."

The parties behind these attacks are quite varied. Some are individuals, others part of a criminal enterprise, and still others operate under the (unofficial) auspices of nations. "It definitely encompasses a lot of people, a lot of nation-states. You see some of these groups sort of doing both," CNBC cybersecurity reporter Kate Fazzini told NPR in June. "So we've had issues with ransomware being deployed by criminals who were also doing some work for the Iranian government or the North Korean government. It's almost impossible to tell right away, and even after a lengthy investigation, it's still very hard to tell."

Turns out, these bad guys don't even need to be particularly proficient in cybercrime to pull off these sorts of incursions. As Akshay Bhargava, SVP of Malwarebytes, points out that part of the overall increase in attacks stems from the ease of entry into the space. While it's no longer a case of simply hopping on an illicit IRQ channel and trading malware code as script kiddies did throughout the early 2000's, "it's easier for smaller actors to participate," he told Engadget. "At the same time, the bigger actors, the more strategic are becoming much more coordinated, much more persistent and well funded to do these things."

Bhargava also notes that more professional groups are spending a significantly larger amount of effort and longer amount of time performing their initial reconnaissance of their targets. This could involve anything from probing a network's defenses to building dossiers on employees for use in spear phishing attacks. "What you're seeing is a lot more sophistication," Bhargava said. "A lot of social engineering, a lot of understanding how to really target the specific company and make it seem very legit." Doing so ensures that when the malware is launched, it lands at a point in the system where it can do the maximum amount of damage in a minimal amount of time.

Unfortunately, those organizations which are attacked don't often have much recourse. There is no singular law enforcement agency tasked with monitoring, much less responding to, these events. The FBI is often the first to be alerted but, again, the agency relies on the organizations being hit to reach out proactively. And even if the Feds do manage to track down those responsible for an attack, unless they live in or travel to a country with a US extradition treaty, there's not much that the FBI can do.

Rather than wait around for the next ransom demand, a number of online security firms have begun to develop proactive defenses against this strain of malware, however their efficacy has yet to be demonstrated. Whether these new systems set off an electronic arms race of tools and exploits remains to be seen but there seems little doubt that ransomware attacks will ever be viewed as a price of doing business.