The rise, fall and return of the smartphone megapixel race

More megapixels, better camera phones?

Sony recently unveiled a smartphone camera sensor with the highest resolution yet, a jaw-dropping 48 megapixels. That's more than the resolution of its $3,000, 42.4-megapixel A7R III mirrorless camera, which has a sensor eight times larger. It sounds great, but you might have forgotten that Nokia's 808 PureView smartphone, with a 41-megapixel camera, was released way, way back in 2012. Why didn't modern smartphone cameras follow Nokia's lead?

As Apple has demonstrated over the years, from the iPhone 4s and forward, you get more benefits with other features, like dual cameras and sensors with bigger, more light-sensitive pixels. Those deliver better low-light shooting, more bokeh, faster speeds, zoom capabilities and improved video. However, Sony now believes you can have all that and high resolutions, too. Its Quad Bayer tech, reportedly used in Huawei's P20 Pro camera, might help big-number megapixels make a comeback -- and this time, they'll be far more useful.

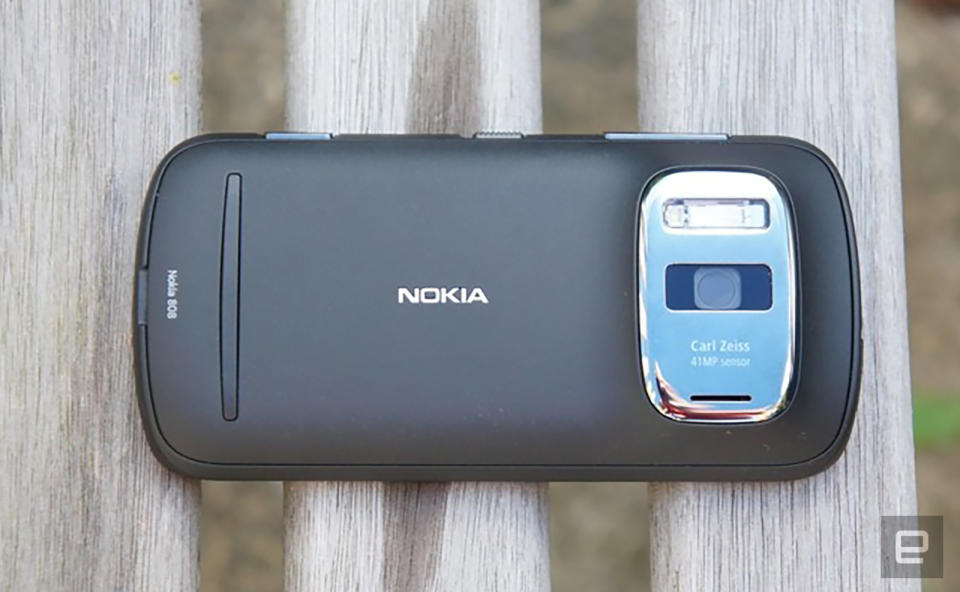

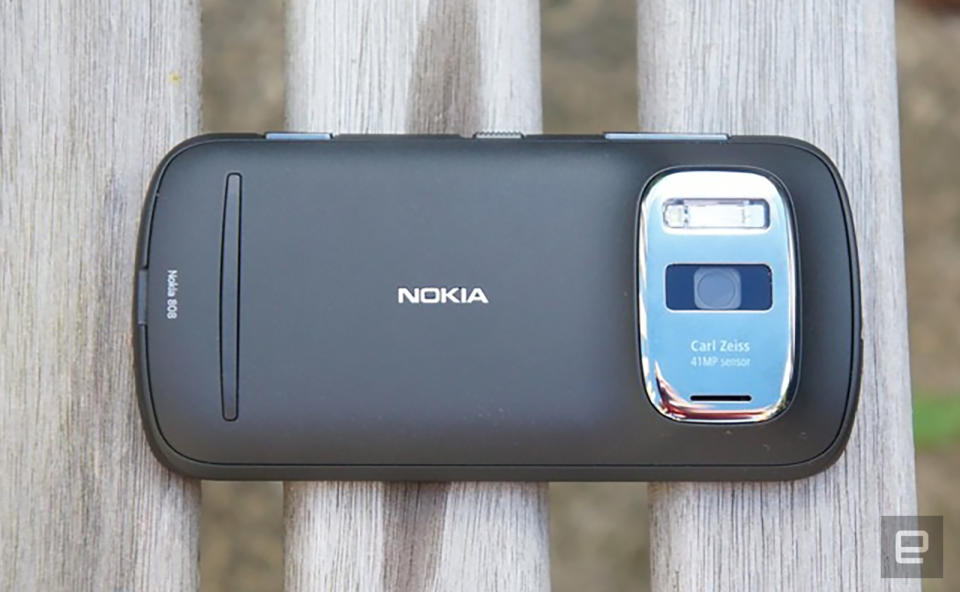

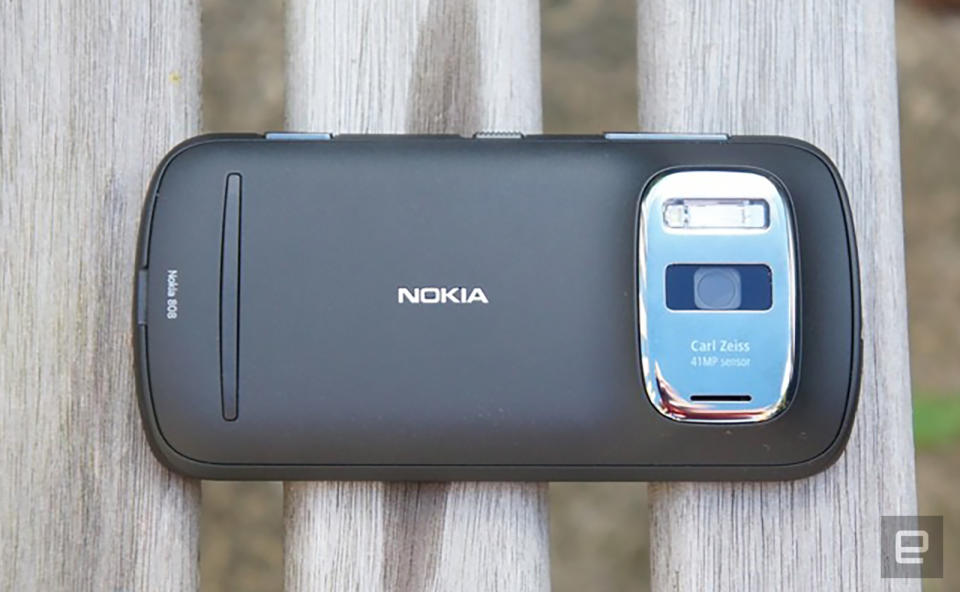

Nokia's 41-megapixel 808 PureView

Smartphone cameras have steadily gained megapixels over the years. In 2010, Nokia unveiled the N8 Symbian smartphone with an "unparalleled" 12-megapixel camera, and that same year, Sony launched the 16-megapixel S006 phone.

In 2012, however, Nokia massively raised the stakes with its PureView 808, a Symbian smartphone with a crazy 41-megapixel camera.

It's frustrating to think that Nokia didn't take better advantage of such cutting-edge technology, but it was a lousy smartphone with a superb camera. The sensor was just under an inch in size, close to those found in Sony's $1,200 RX100 Mark VI camera. It was also equipped with an f/2.4 Carl Zeiss prime lens, a great mechanical shutter with a dedicated button and digital zooming that was actually useful with all that resolution.

While you could take full-resolution shots at 38 megapixels, your best bet was shooting eight-megapixel PureView shots. PureView oversampled the full sensor to deliver smaller, razor-sharp images with minimal noise. It also used the same tech to give you lossless zooming and capture 1080p video at up to 30 fps with stunning quality.

"It's clear that Nokia's 808 PureView represents a revolution in terms of stills and video performance -- not just for camera phones, but for the entire imaging industry," Engadget's Mat Smith said.

Low-light performance was also "spectacular" for the time, he added. Despite the high resolution, the large sensor had 1.2 micron pixels as large as the ones on its then-rival, the eight-megapixel HTC One X. Combined with PureView's oversampling, that yielded relatively noise-free images in dim shooting conditions. Its low-light shooting performance is underwhelming compared to 2018 smartphones from Apple, Samsung and Huawei, but that's more about the leaps in sensor technology in the last six years.

The big problem with the 808 PureView was the terrible, aging Symbian software that powered it, which we called "laughably tragic." Another issue was the form factor -- most smartphone cameras have 8mm sensors, and Nokia's was nearly three times larger (1/1.2 inches). That required a bigger lens that made for quite a hump at the back. "Nokia's phone more closely rivals a point-and-shoot camera in size than a smartphone," we said.

The four-megapixel HTC One

It might seem hilariously retrograde that HTC released the One with a four-megapixel camera just a year after Nokia built the 41-megapixel 808 PureView. However, both devices, via different means, delivered great low-light photography.

Images snapped with the Nokia model were noisy at full resolution in low light, but when oversampled down to eight megapixels, much of that was eliminated. The HTC One's "UltraPixel" camera, by contrast, had much larger pixels (2 microns compared to 1.2 microns) that could grab nearly 300 percent more photons.

Combined with a fast f/2.0 lens and optical image stabilization, the One "outshines almost everything else in low-light situations," Engadget's review affirmed. The exception? "[It] comes in second only to the current imaging king, the Nokia 808 PureView." HTC's camera also excelled in video, and unlike the Nokia 808, could grab HDR video at 1080p -- one of the first smartphone cameras with that capability.

Nokia's 41-megapixel Lumia 1020

The 2013 Lumia 1020 had an identical camera and capabilities to the 808 PureView but was equipped with Windows Phone software rather than Symbian. That seemed like a great improvement at the time, but as we now know, Microsoft bought Nokia just a year later, and its mobile business subsequently collapsed.

As such, the Lumia 1020 was the pinnacle of large-sensor smartphone cameras, arguably until the Huawei P20 Pro came along. Smartphone makers have kept sensors and lenses small enough that you don't need a hump, turning to other types of tech to help you make better photos. Apple, which sells more smartphones than any other company, is a great example of how that went.

Apple's iPhone camera progression

Design-sensitive Apple would never have created a smartphone as awkward as Nokia's PureView, even if it would have yielded the greatest camera ever. Rather, it used cutting-edge imaging tech to gradually improve its lauded iPhone cameras. As such, they're an interesting way to view smartphone camera technology development, excluding sensor resolution, over time.

Apple's first great photography smartphone was the 2011 iPhone 4S with an eight-megapixel camera, which had solid optics and an easy-to-use interface. It ramped up the tech with the eight-megapixel iPhone 5s, bringing a larger sensor area for cleaner low-light shooting, an f/2.2 lens, True Tone flash for better white balance, autofocus matrix metering, digital image stabilization, 120 fps slow mo, and more.

The iPhone 6 Plus brought optical image stabilization, but the 2015 iPhone 6S camera had the first big resolution leap since the iPhone 4S, with 12 megapixels. It was also the first iPhone that could shoot 4K video.

Apple then took a different direction: The iPhone 7 Plus was Apple's first dual-camera smartphone. Both had 12-megapixel sensors, but one had a wide field of view, and the other a 2x zoom (Huawei and LG were ahead of it with dual cameras, though). On top of the zoom capability, the cameras allowed you to blur out the background to create soft bokeh behind the subject. The cameras on both the iPhone 7 and 7 Plus also packed f/1.8 lenses and much faster, more advanced image processors.

The current iPhone X and iPhone 8 Plus are the pinnacle of Apple camera design. Each has dual 12-megapixel cameras, with f/1.8 and f/2.4 lenses for the 1x and 2x zoom cameras, respectively. The iPhone X has optical stabilization on both cameras, while the iPhone 8 Plus has it on the 1x lens only.

Your high megapixel future

You'll notice that the big smartphone players have never gone big on high-resolution sensors, despite the 2012 Nokia's 808 PureView's great camera. Rather, they focused on tech that improved cameras in other ways, while still allowing the slim factors that consumers wanted.

So it was surprising to see the Huawei P20 Pro's 40-megapixel triple camera, and then the 48-megapixel IMX586 sensor from Sony. Looking back at the evolution of smartphone cameras, though, it all makes perfect sense.

As Sony implied in its press release, it's always better to have more resolution. In decent lighting, you can zoom in digitally up to four times on a 48-megapixel image and still have a sharp 12-megapixel photo. You can also supersample the full 48 megapixels down to a lower resolution to increase sharpness and color accuracy.

At the same time, Sony's sensor offers more light-gathering power without the need for supersampling. In low light, the Quad Bayer color filter array can add the signals from four adjacent pixels, multiplying the light received by a power of four. While that reduces the resolution to 12 megapixels for night shooting, you can crank it up to higher resolutions during the day, having your cake and eating it, too.

Huawei's P20 Pro, which uses similar tech (and possibly a Sony sensor), points the way to a high megapixel future. For one thing, you can capture extremely high-resolution images via the 40-megapixel camera. The Quad Bayer-like sensor doesn't produce images as sharp as those from a regular Bayer filter, but they'll still be sharper than with any other current smartphone camera. Should you decide to crop a shot after the fact, you'll have a lot of pixels to work with.

When it comes to the crucial zoom, if you want to take a clear telephoto shot, you can also use the eight-megapixel, 3x (80mm equivalent) camera. To zoom in even further, the eight-megapixel and 40-megapixel cameras work together, giving you a 5x zoom that's miles ahead, quality wise, of any other smartphone, as we found during our P20 Pro camera test.

At the same time, the P20 Pro can also shoot great HDR images. The 40-megapixel camera appears to take two photos with different exposures at the same time, then marry them afterward. Other smartphones take one photo after another, which can result in blurred images.

On top of that, it has a 20-megapixel, non-Bayer monochrome camera that takes great black-and-white photos, while boosting low-light color shooting capability. Bear in mind that Sony's new sensor is less than half the size of the 1/1.7-inch model on the P20 Pro, so it's not likely to be as good in low light. In fact, at 8mm, it's just a shade smaller than the sensor on the iPhone X.

Still, Sony's sensors are widely used in smartphones, so if other manufacturers elect to use the IMX 586 imaging sensor in much the same way as Huawei, we'll soon see devices with incredible new camera capabilities. At the same time, the small chip size will ensure very slim and lightweight devices. Thanks to the evolution of dual camera technology, canny algorithms and informed designs, high-resolution smartphone cameras might finally come to phones many of us will actually buy.