It's time to talk about mental illness in indie development

Success can be just as heartbreaking as failure.

This is normal.

Heart pounding, hands shaking, head packed with static. The absolute inability to process what anyone is saying, let alone respond to it. Sitting alone at home -- lights off because you've been inside all day and the sun set hours ago, but your legs have been glued to the chair for just as long -- computer screen glowing. Wanting to be outside but unable to deal with the idea of people, conversation, smiling, pretending. Feeling worthless.

This is normal.

That's the message Kate Edwards and Mike Wilson are trying to cultivate in the independent game development community. Depression, anxiety and other mental illnesses are common, and any person feeling this way is not alone.

"This is part of development, it's normal," Edwards says.

"It's abnormal to not feel this way," Wilson adds, nodding.

Edwards is executive director of Take This, a five-year-old non-profit organization dedicated to helping people in the video game world talk about and manage mental illnesses. Wilson is the co-founder of Devolver Digital and Good Shepherd Entertainment, two powerhouses in the realm of indie publishing. He deals directly with indies every day, and when he met Edwards, Wilson had seen four developers under his labels hospitalized for mental health problems in just two years.

With this reality as their connective tissue, Edwards and Wilson hit it off. In March, Wilson joined the board of Take This.

"We talk about stigma and, yeah, there's a huge societal issue there, but I think just for developers, they need to understand this is normal," Edwards says. "There's all kinds of other normal things we can talk about with indie development and having to market yourself, but this is one aspect that's normal, and it's much more prevalent than people think."

"It's like bugs in your game," Wilson says. "They will exist, I don't care who you are. You will fuck something up, and you will need to fix it, and you are also going to have bugs."

"Mental bugs," Edwards says.

The indie institution

Take This was founded in 2013 by video game journalists Russ Pitts and Susan Arendt, alongside clinical psychologist Dr. Mark Kline. Pitts and Arendt were shocked into action after the suicide of a colleague in 2012, and they started the Take This blog to discuss mental illness in the video game industry. It hit a chord, and the blog blossomed into a non-profit that provides resources and panels on the benefits of having an open dialogue about mental illness. Plus, it publishes white papers on harmful game development practices and hosts the AFK Room at major gaming conventions across the country, offering quiet spaces staffed by licensed clinicians for anyone feeling overwhelmed by the bustling, noisy floors at PAX and other big shows.

Though Take This is concerned with broadening the mental-illness conversation across the video game industry, from AAA to one-man dev teams and even journalists, Wilson is specifically invested in the health of indie developers. Edwards is, too -- she was executive director of the International Game Developers Association from 2012 to 2017, and she's seen first-hand how the indie lifestyle can contribute to depression, anxiety and other illnesses.

Independent development has become a mainstream pursuit over the past decade. High-profile successes, the advent of digital-only publishing and accessible game-dev tools have pushed the indie industry into the spotlight, with triumphant developers pulling in millions from a single title, seemingly overnight. Yet there are even more developers who spend years building a quality game, expecting the big indie payoff, only to see sales fall well below such high expectations.

"In my perception of the last few years, it has gotten worse because the stresses of success are something I think a lot of Indies are not prepared for," Edwards says. "Well, actually the stresses of both success and failure. We've seen it on both sides."

The stress of success

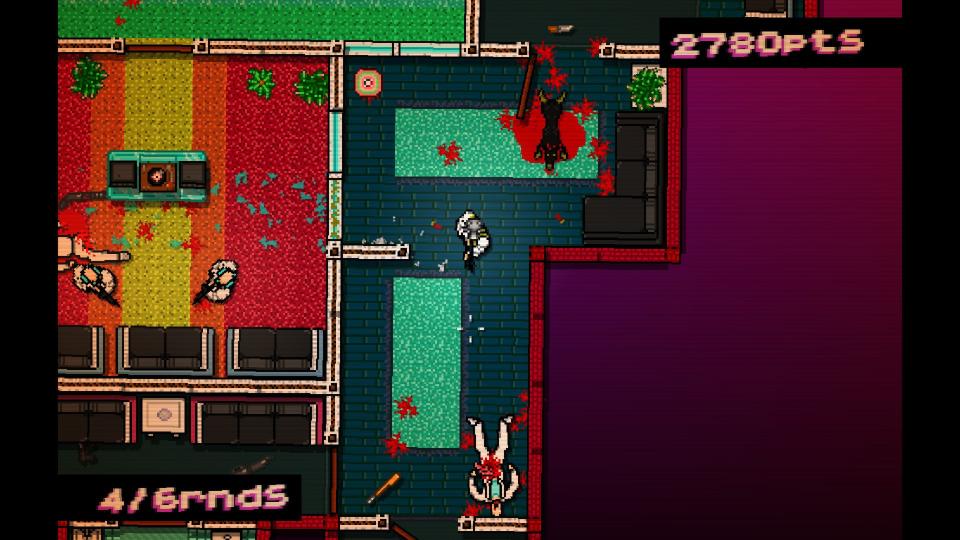

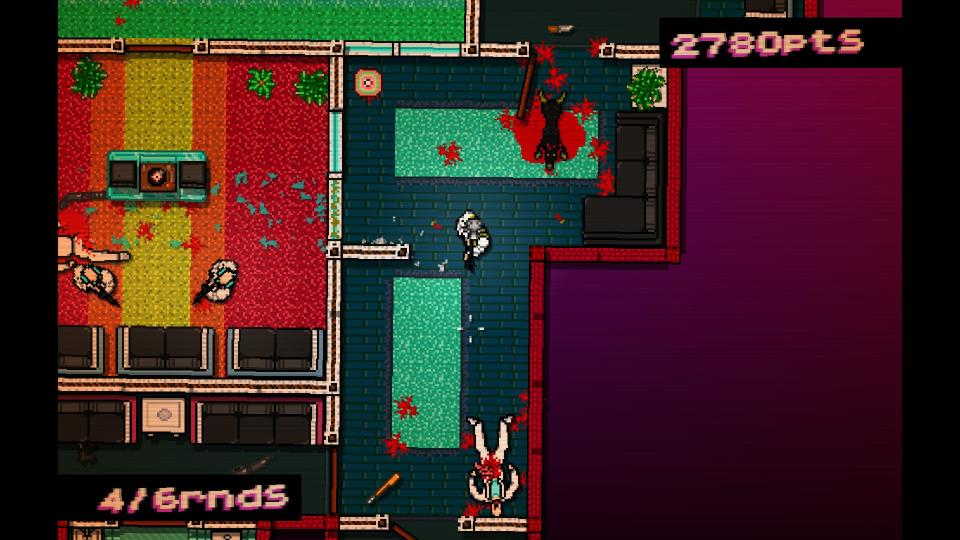

Hotline Miami is a perfect example of the modern indie mental toll. The game hit Steam in 2012, the brainchild of two-man development squad Jonatan Soderstrom and Dennis Wedin, and published by Wilson's Devolver Digital. Hotline Miami is the game that put Devolver on the map as an indie publisher -- it was an immediate, massive success, selling 300,000 copies on PC in its first four months alone. It's an ultra-violent, neon-splattered, top-down action game set in 1989, complete with a trippy storyline involving the Russian mob, mysterious janitors and a series of power-endowing animal masks.

"Dennis completed some of those levels of Hotline from an institution," Wilson says.

Wedin was hospitalized for two weeks during the development of Hotline Miami as he dealt with the end of a romantic relationship.

"I was super depressed during the first game because of my breakup, which was really rough on me," Wedin says in a Hotline Miami documentary produced by Complex. From the mental health ward, he infused the game with personal tidbits from his relationship -- but neither Wedin nor Soderstrom told Wilson about the hospitalization. He only found out about it because he watched the documentary.

Wedin didn't want anyone at Devolver to worry, Wilson says.

"We were always worried about his partner, Jonatan, because he looked the part," he recalls. "Dennis is the gregarious rockstar, he's got a tan, he's not afraid to travel and talk to press, and the other one is like you're trying to listen to a game developer."

This was a wake-up call for Wilson. There's no physical indicator for mental illness, no solitary mold of person that it affects. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, one in six adults in the United States lives with a mental illness -- and, of course, they don't all look or act the same way. Sometimes, there is no red flag.

Wedin's hospitalization went down before Hotline Miami became Hotline Miami -- before it turned Soderstrom and Wedin into rich, big-name indie developers. After the game came out, their lives changed dramatically, but not necessarily for the better.

"It's really hard to feel bad about it because you know you're privileged to be in this situation, but at the same time, I don't like my life more now than I did before the game," Soderstrom says in the Complex documentary. "I kind of like it less."

"Yeah," Wedin agrees.

Soderstrom continues, "I can't feel sorry for myself. I feel like an asshole for not taking responsibility for my life. But I don't know what to do about it. It's just a natural thing that I do. And it wasn't supposed to be a big game. It was supposed to be a great game for a very select few people."

"For us," Wedin says. "We made a game for us."

Take This into the future

Wilson is aware of four Devolver and Good Shepherd developers in the past two years who have been hospitalized for mental illness, but he knows there are more stories out there, even more people wrestling with their demons alone.

"How many people have suffered in silence?" he asks. "Or lost their girlfriend or boyfriend or husband or kids?"

"It's still a massive pyramid of people," Edwards adds.

"Anxiety for AAA developers is significantly different from anxiety for indies."

Indie developers face a specific brand of pressure, much of it internal. Edwards admires the drive that she observes in these folks, but she also sees how the common indie workflow can push developers deeper into their own minds, driving negative introspection and forcing isolation as they try to finish their games at any cost.

"Anxiety for AAA developers is significantly different from anxiety for indies," Edwards says. "For the AAA developers, often it's the deadline, it's the manager, it's the performance review. ...But in the indie space, it's the same anxiety as the entrepreneur or small business owner has."

Online tools have made it easier than ever for folks to work from home, but this evolution can be a double-edged sword, keeping developers from engaging with nature, friends, strangers and the non-digital world in general. Edwards recalls an encounter with a specific developer who exemplifies the everyday, overworked indie:

I happen to know they're extremely introverted, as many people in this industry are, which just compounds the problem. I saw them and I could just tell -- I had known them long enough, I could tell they were having issues and I just gave them a big hug, and they just started crying like crazy.

They said, "You're the first person who has hugged me in months."

Here's where Take This comes in. Its mission is to let developers like this one know that they're not alone, and provide resources for them to improve their mental states. The organization offers resources for finding a therapist, taking antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications, and even supporting friends who are dealing with a crisis.

Take This received a grant this year from Child's Play, a large charity that provides video games to kids in hospitals, to help it implement the AFK Room at every PAX convention in North America. There are plans to expand the AFK Room to other conventions, as well. To further aid in this goal, Take This recently established a crowdfunding campaign seeking $50,000 by April 30th.

There's also the new Take This Ambassador Program, which aims to train YouTube and Twitch streamers in discussing mental illnesses, so they can better manage their own crises and pass along valuable information to their audiences. The program is due to roll out this year.

"They're willing to talk about it, that's the most important thing."

"One of the things we've had happen over the last couple of years is we'll have streamers and YouTubers approach us and they really resonate with our mission," Edwards says. "They say, 'I'm suffering from mental health issues, I'd love to talk about it on my show, but I'd like to stream for you, I'd like to raise money for you.' It's just so cool to see that happen. We're talking a few hundred bucks, maybe a thousand or so, we don't care. The fact is that they're willing to do it and they're willing to talk about it, that's the most important thing."

Take This is building an army of indie developers and streamers who are equipped to help people -- and themselves -- through mental illnesses. It all starts with conversation.

"They're not afraid to read some instructions and follow them and master something new, but that has to exist and the conversation has to exist," Wilson says. "Saying that it's normal is the perfect thing."