The science behind the 'beats to study to' craze

Brain.fm claims its AI-generated tracks can help you concentrate.

I sit at my desk at least eight hours a day. Between the steady pings from Slack, my trusty group chat and the siren song of the greater internet, staying focused can be difficult. As I write this, I'm swiping between a full-screen Scrivener window and a full-screen Chrome window because... I honestly don't know. Some people listen to podcasts at work to make mindless tasks go by. Unfortunately, I can't simultaneously pay attention to a conversation and write, so to help combat the incessant distractions, I listen to music -- a lot of it. Usually I turn to original scores from movies and video games, but I switch it up with instrumental hip-hop, industrial and downtempo electronic.

A side effect of my efforts to fight against distraction is that I'm always on the lookout for new music to help me focus. And I'm not alone.

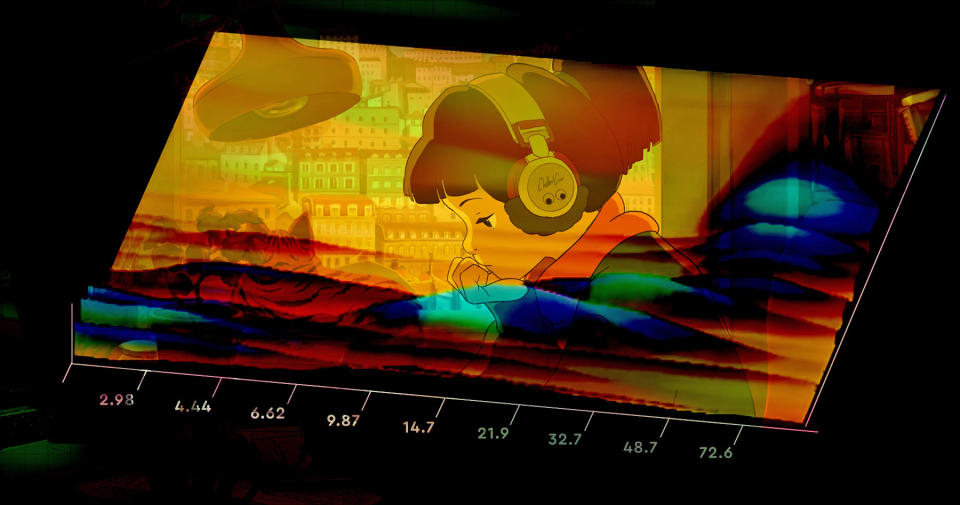

Tune into ChilledCow's "lofi hip hop radio - beats to relax/study to" on YouTube at any given moment and you'll find thousands of people watching simultaneously. But it's not the visuals people are interested in -- it's the music. Every copyright-free track on the never-ending playlist sounds like the type of tune you'd put on at a backyard barbecue: mellow beats with an analog flair. Over the past three years, ChilledCow's channel has amassed over 74 million views. There's just one problem: It didn't exist when I started writing a decade ago, so I had to find my own music to study to.

When I started my search, I quickly discovered that Slayer didn't help me concentrate, and that, combined with how bored I was with metal after a lifetime of listening, I was ready to expand my musical horizons. Two years into this journey, Trent Reznor and writing partner Atticus Ross released their Academy Award-winning score for director David Fincher's Facebook origin story, The Social Network. I wrote to that album for three years, exclusively, and to this day it remains my go-to music when I'm on deadline.

The instant the opening track starts, with its unsettling housefly drone and a melancholy piano melody, my brain knows what time it is. By the time the beat drops on second song, I'm nodding my head along, fingers pounding at the keyboard. I love the album because it's sparse enough to fade into the background while I bang away at a draft, and there are enough layers to hold my attention when I listen AFK. But despite how intimately acquainted I am with the album, I can't tell you what makes it my perfect working music.

Reznor has said that when he's writing a pop song, he wants all your attention on the hook, but when he's writing a film score, that isn't the point. There, he's either trying to underscore or punctuate emotion. Perhaps that's what makes the music I've been listening to ideal for working: It's not meant to draw attention to itself. But that's only half the battle.

"Just making something that's not distracting is not enough," Brain.fm's Kevin Woods told me. Woods has a PhD in auditory neuroscience and serves as the company's director of science. Brain.fm makes "functional music" and uses AI to tune it specifically to activate neuron activity associated with focus, meditation and relaxation. I wasn't aware of ChilledCow's channel until a few months ago, so in March when I heard about a service explicitly designed for focusing, I was intrigued.

The app was designed to be a shortcut to the years of listening I've done. The pitch: Within 15 minutes of listening, its music will lull you into a mental state that doesn't divert your attention. Its preliminary research (currently in peer review) suggests that, over time, Brain.fm's music becomes even more effective. Currently, the app's focus section offers around a dozen of musical themes with choices for movie soundtrack-inspired, electronic and, the most notable recent addition, "grooves," which attempts to emulate analog hip-hop. When you start listening, you can pick from an endless session for those late nights, or a 30-, 60- or 120-minute track.

The company's on-staff composers pick the key a song should be in, the instruments used and how it should sound overall, writing it out using a piece of custom software designed by Brain.fm co-founder Adam Hewett. After they're done, an AI assembles the pieces and stretches them out over the desired length of time, adding in the mental-state triggering frequency modulations when it sees fit. "The human is controlling the artistic integrity, and the AI is imposing the science," Woods explained.

I wanted to find out exactly what made the music I work to so suited for the task, so I sent Brain.fm a dozen of my go-to picks and asked Woods to analyze them against his checklist of traits for desirable focus music. My selections ranged in style and genre, but shared the common theme of minimal, if not entirely absent, vocals. No single album checked all of Brain.fm's boxes from start to finish, which isn't surprising: They weren't crafted to make me more productive; they're artistic expressions that also happen to keep me focused.

But from J-Dilla's hip-hop magnum opus Donuts to German black metal act Urfaust's ethereal Empty Space Meditation, with soundtracks for It Follows and Bastion in between, all the albums I submitted exhibited multiple focus-friendly characteristics. One particular song from The Social Network matched Brain.fm's rubric nearly to the letter. After spending time analyzing my music, Woods said it "totally made sense" from a scientific perspective that this music works so well for me.

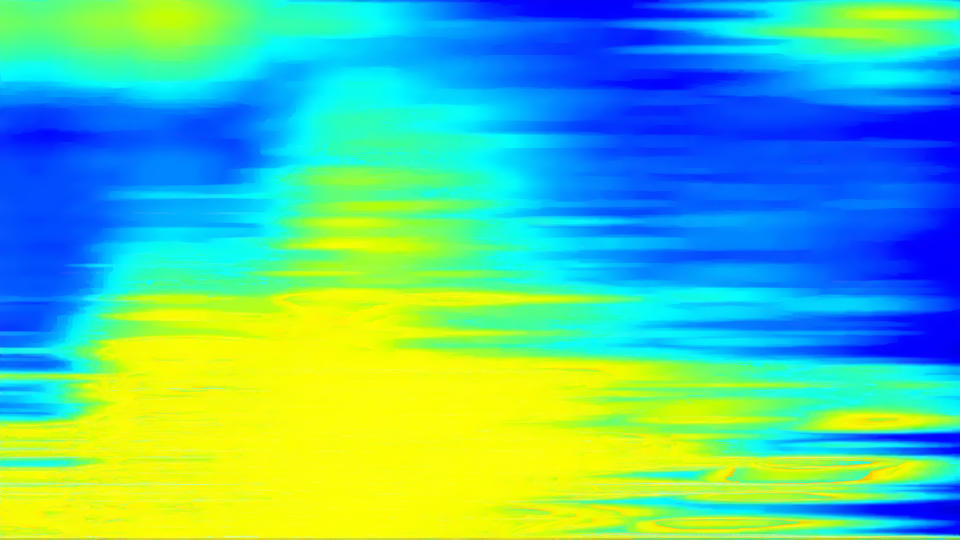

According to Woods, good focus music has no vocals, no strong melodies, 'dark' spectrum, dense texture, minimal salient events (more on that later), heavy spatialization, a steady pulse, sub-30-200Hz modulation and above 10-20Hz modulation. Brain.fm's music checks all those boxes. Ideally, focus music is going to have a drive and energy. You want a sense of motion in the music, not just something light and airy. That's the difference between Kid Koala's beautiful Music to Draw To: Satellite and most everything else I sent Brain.fm to analyze.

Woods called the Canadian DJ's record a "great example" of music that might be perfect for creative work, but not necessarily concentration-intensive tasks. "It's like music for daydreaming," he said. "But it's not music for focus. It doesn't have that sort of drive and energy. You want that sense of motion in the music." To create that motion, Brain.fm will take a beat from a dance song, or, say, a Hans Zimmer-style orchestral score and reduce the treble and minimize any other distractions in the music. What's left are the bones of the song, sanded down to only the essential parts needed to spark attentiveness.

Reznor and Ross' take on "In the Hall of the Mountain King" ranked worst among the tracks Woods' analyzed. It lacks a steady pulse, favoring stabs of strings over subtle textures. More than that, the mere mention of the Edvard Grieg piece likely calls to mind its frantic melody. Its biggest offense is the number of distractions. Reznor and Ross' arrangement trades cymbals for high-pitched fuzz, but it's no less distracting, or, if played on repeat, annoying. Reznor jokes that the three weeks he and Ross were working on the song in his home studio almost ended his marriage.

Science refers to that quality as a "salient event." A baby crying or a dog barking are salient because they're piercing and change volume. A steady drone is easy to ignore because after a certain point the brain tunes it out. The sound doesn't disappear -- you just stop noticing it. Reznor and Ross deliberately manipulated this. "Why do [you] feel uneasy? Well, it's because there's been this thing you haven't noticed that's been gnawing at your nerves," Reznor told The New York Times.

Woods drew from scientific studies on salience to create an algorithm for generating music that never pulls you out of your desired mental state. His assessment of "Mountain King" made a lot of sense because as soon as that song comes on, I'm immediately aware that I have music on in the background and that the album looped. I recently deleted the track from my Google Play Music library, and it's been smooth sailing ever since.

One recent morning, I started an endless "underwater" session on Brain.fm. My news shift flew by and I was noticeably more productive, writing a few more posts than usual and clearing my inbox before I closed my laptop for the day. Great, right? The problem is, I didn't feel that I was 'in the zone' like I do when I'm on a streak -- it felt like I was in a trance. It wasn't comfortable. That might have something to do with the fact that I subjected myself to nine hours of Brain.fm's trademark trick: low-frequency envelope modulations.

These amplitude modulations work based on "forward masking." Meaning, if you hit a snare drum, for a moment afterward your ear is less sensitive to everything else. "Amplitude modulations are helping you drown out background sounds while keeping the music at an overall even level," Woods explained. The low-end modulations sound like helicopter blades, a low thrum vibrating louder, then softer, between 10 and 20 times per second. If the modulations are too slow, like the bass drum in a 4-4 rock beat for example, you're pulled out of focus because your brain is anticipating each kick. Speed it up and your brain more or less stops caring.

"There's a good reason to care about amplitude modulation," Woods said. "You can go into the brain and poke neurons and you can see that they'll respond to changes in amplitude rate in a very specific way." He added that there are populations of neurons in the brain specifically tuned to react to the frequency modulation spectrum. "Which is why we care about them," he said.

Maybe that's why I don't fall into a trance-like state looping The Social Network. Because it's imperfect by design, my brain isn't constantly locked into focus. The lack of dense textures from "In Motion" and the absence of low-frequency amplitude modulations in "Carbon Prevails" actually do my neurons a favor.

Headphones vs. speakers

Much to the chagrin of my neighbors, I don't use headphones at home. I like having music in the background when I'm working. My stereo and tower speakers reside in the living room, separated from my office by a thick plaster wall. Wearing headphones puts the music front and center; it demands my attention. I'm acutely aware that I have something on my head or in my ears, and it blocks out the rest of the world. Great for a cross-country flight, but not useful when I'm working from home. I like hearing my keyboard as I type; the music helps drown out all the other noises.

Even with Brain.fm's music running through headphones at my desk, I had a hard time concentrating. It wasn't until I streamed the tab to my Chromecast Audio (connected to my stereo in the adjacent room) that it clicked for me. Apparently, I'm extremely sensitive to reverb and its effect on music. As you put more physical distance between yourself and a sound source, the reverb increases. Woods said that for an extreme example, if I wanted to really increase the reverb, I should flip my speakers so they're firing at the wall. It'd make the sound muddy, but it'd decrease the contrast between sounds, helping it fade into the background even further.

"Having everything a little less crisp prevents it from grabbing your attention," Woods said. "Decreasing the crispness of the sound, especially in the time domain, is going to reduce the attentional draw to that sound, decreasing the salience."

Essentially, because my speakers are in the other room, rather than on my skull, anything I listen to that way is going to be more suited for focus. It becomes a constant hum that masks everything else.

Since 2013 I've listened to The Social Network 226 times via Google Play Music. That's not counting those first three years of listening on my now-dead desktop PC, a CD and the Halo 3-branded Zune for which I lost the charging cable.

The score keeps a movie about friends screwing each other out of billions of dollars moving at a brisk pace and Aaron Sorkin's machine-gun fire script grounded. Reznor's method for the record shed a few clues about why it works for me.

"We needed something that sounds like a spark of creativity, of acceleration," he said during a press tour interview in 2010. "You've got a good idea, and you want to follow it to its course. [It's] that excitement." During that same fireside chat, supervising sound editor Ren Klyce agreed, describing one song in particular as sounding "percolating, like wheels moving in [Zuckerberg's] head."

When Woods told me the album's fifth track, "Intriguing Possibilities," checked off all the boxes for desirable focus music I was caught off guard. It wasn't perfect (Woods said it could use more frequency modulations), but it's a "close match" for Brain.fm's AI-generated songs.

At first I didn't believe him. And then, embarrassingly, I had to quickly queue the song up so I could figure out which one it was. Even after all the listening I've done, I still can only associate names with album opener "Hand Covers Bruise" and then "Mountain King." The rest have bled together by this point; I identify them by musical passages, not names or track order.

I looped the song for an evening while working on this piece, and I felt similar to how I did after a day with Woods' music. Because it's only 4:24 long and doesn't loop well at all, I was keenly aware of each time it repeated, giving my neurons a break at a quick interval. The trance-like sensation wasn't nearly as intense as it was with the AI-generated tracks, but I felt it nonetheless.

Overall, Woods' analysis of The Social Network was that it's the best option of all my go-to music (with Darksiders II coming in close second), even if some songs didn't have any dense textures or enough spatialization. At this point, I'm so familiar with the music that any distractions from Woods' perspective as a first-time listener are moot. There's also the mental association I have with the album. Because I've made it my default task music for the past eight years, there's a Pavlovian effect and my brain knows it's time to buckle up. "If there's a track you've been listening to all your life and it's new for me, it's going to be more distracting for me because it's new," he explained. "People are different. Their experiences are different."

After Woods had analyzed my music, I asked if he'd take a look at some songs from one of ChilledCow's playlists. This time, it was Woods who was surprised.

Woods speculated that the big reason this channel is so effective doesn't have anything to do with scientific parameters like specific frequency modulations or a lack of salient events. Instead, it's more organic. It's the emotion in the music itself, which doesn't have to do with frequency filtering or fancy auditory tricks, that's so important. It has to do with the actual notes and rhythms that are being played. "It suddenly seems that one of the more important things really is music theory," he said. "That's something we can never discount; there's really no substitute for that."

Woods added that the sub-genre sacrifices some features of his rubric to emphasize others. So, while a snare hit might be a salient event, its presence begets a heavier than normal sense of spatialization. Meaning, a production technique that tricks you into thinking a sound is coming from a physical space rather than a recording. "It's a trade-off that apparently works really well for some people," he said. The end result is feeling like you're wrapped in a bubble of the music, with hip-hop's reliance on looped beats helping the music to gently fade into the background.

"People sometimes need to wind down to work best," Woods said. "The energetic, aggressive work music we discussed [previously] is a solution to a different problem."

Things like jazz chords and vinyl noise evoke an emotion rather than agitating a neuron

All of his parameters for good focus music are understandably clinical. "These acoustic features I've been talking about, they're things about sound, not things about music," he admitted. "The world that musicians live in has key signatures, time signatures, major and minor keys. I haven't been talking about that at all, but what this 'lo-fi' [channel] shows is those things can be enormously important."

Things like jazz chords and vinyl noise evoke an emotion rather than agitating a neuron. Woods is keenly aware of the balancing act between crafting effective focus music and the artistic medium's inherent ability to manipulate your emotions. He theorized that's another reason why ChilledCow's audience is drawn to the genre: It's popular for its ability to set a mood rather than its impact on motivation and distraction.

The constant high-frequency hum of vinyl acts a "blanket," according to Woods, and all the other sounds in the mix lay below it. Because of its presence, a snare hit or guitar strum isn't as jarring. He said one of the easiest ways to cut back on musical surprises is to add in a constant. In this case, the constant is the aural byproduct of a needle rubbing on plastic. That's probably why some people insist "vinyl just sounds better," but can't articulate why when asked.

The gentle hum of vinyl also subtly draws on a cultural association: nostalgia. Woods said that the production techniques used with lo-fi analog recordings draw on our memories of simpler times. He also theorized that people choose the channel because they have a reaction to rain, which is a common theme among many lo-fi tracks. When you think about it, it makes sense: Plenty of people sleep better when it's raining, and the light, almost fuzzy pitter-patter of the precipitation shares a lot of qualities with vinyl noise.

Brain.fm's interpretation of lo-fi doesn't add vinyl noise. Instead the team subbed in pads, "noisy synthesizers," to create dense, constant textures that in theory serve the same purpose as vinyl noise. This emulation of the lo-fi genre is representative of a larger issue: Right now, you can't give an AI a soul. Rather than it feeling like I'm spending a rainy day inside, listening leaves me feeling flat and cold. On paper, Woods' music might hit all the marks, but in practice it sounds synthetic. It's more or less an emotionless clone. It's not Oscar-winning art; it's content.

I'll never turn Brain.fm on for anything other than its intended purpose. And even then, only for a few hours at a time to avoid feeling like a zombie. But at least the company's science has taught me why the music I listen to already is a perfect fit for me.