Facebook, Twitter and social media’s road to federal regulation

And Google too.

The extent of Russia's meddling in the 2016 US presidential election remains unclear, but it's no secret that social media played a major role. This year brought with it a great deal of scrutiny for tech giants, particularly Facebook, Twitter and Google. These three companies came under the US government's microscope after news that Kremlin bots and trolls, spearheaded by a group known as the Internet Research Agency, used their sites to tamper with the 2016 presidential election. They spread misinformation (fake news!) and dubious ads across Facebook, Twitter and Google to hundreds of millions of users in the US, with the aim of fomenting hostility among Americans. And it's safe to say they succeeded.

In October, Facebook revealed to Congress that more than 145 million Americans were exposed to Russian-linked pages and ads in the lead-up to the election -- a revelation that laid bare the scope of the Kremlin's misinformation campaign. That, as it turns out, was actually more damaging than originally disclosed: Facebook first said that 10 million people had seen these types of ads. Twitter discovered more than 2,500 accounts linked to the Internet Research Agency, while Google found Russian-bought ads on its most popular platforms, including Gmail and YouTube.

As a result, Facebook, Twitter and Google were summoned to testify before the House Judiciary Committee and Senate Intelligence Committee this fall. Members of Congress sought answers about the extent of Russia's influence during the 2016 presidential election and the role technology played in it, particularly social media platforms. During the hearings, lawyers for Facebook, Twitter and Google were asked by members of the Intelligence Committee about their failure to control Russian bots and trolls from spreading misinformation.

The main point of concern for the committee was the number of deceptive political ads that people potentially saw, including one of Aziz Ansari holding a sign that suggested that you could vote from home using a hashtag. That advertisement as well as thousands of others that hit Facebook and Twitter were targeted at Hillary Clinton supporters.

The plan, it seems, is to trust more actual humans to filter malicious content rather than the algorithms that have already failed us.

Facebook General Counsel Colin Stretch testified that the company is deeply concerned about these threats and is already doubling its engineering efforts to crack down on these "bad actors" going forward. He said Facebook is hiring more ad reviewers and requiring more information from political advertisers, including proof that they're affiliated with a campaign.

Twitter and Google echoed Stretch's statements: They both told the Intelligence Committee that they're working to ensure that the events of 2016 don't repeat themselves in future elections. The plan, it seems, is to trust more actual humans to filter malicious content rather than the algorithms that have already failed us. Sean Edgett, Twitter's acting general counsel, said the company is "sharpening its tools" and plans to be more transparent with users and the government in the future. Meanwhile, Google's Richard Salgado, director of law enforcement and information security, said the company is working on systems that can better detect fake news and fake accounts across its ecosystem.

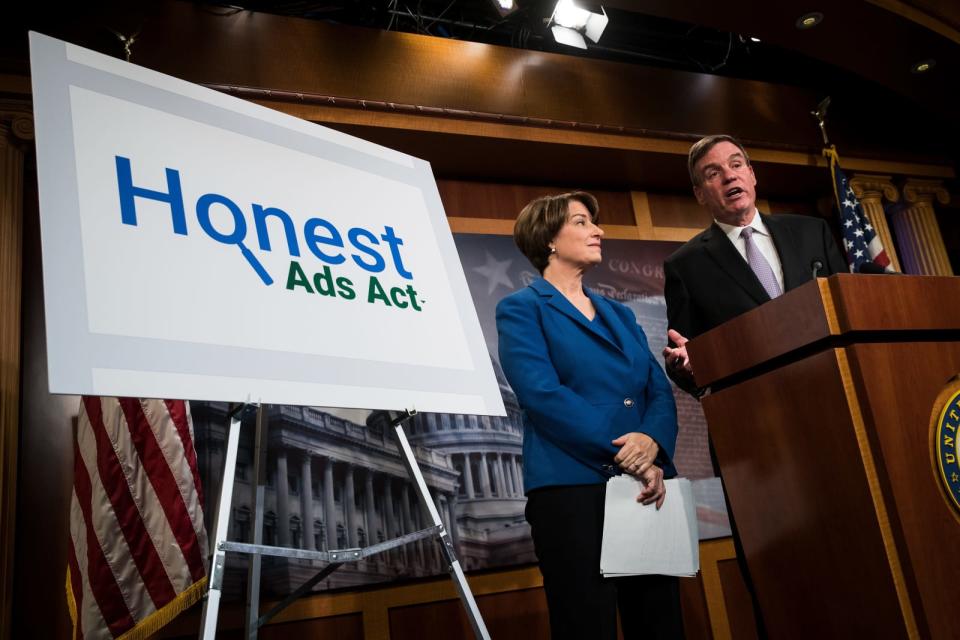

Still, despite promises from tech companies that these issues are being addressed, recent events raise an urgent question: Should the government start regulating political ads and speech on Facebook, Twitter and Google? There are lawmakers on both sides of the aisle who believe so. Indeed, there's already legislation being proposed. With the Honest Ads Act, for example, the government is proposing that online advertising be regulated the same way print, radio and television are. This would require more transparency from the likes of Facebook, Twitter and Google about who's paying for political advertisements on their apps or sites.

Senator Mark Warner (D-VA) told NPR earlier this year that the bill, which he introduced alongside Senators John McCain (R-AZ) and Amy Klobuchar (D-MN), was born after months of asking social media companies to "come clean" with the level of Russian interference that took place in 2016. "We don't want to slow down innovation. We don't want to slow down individuals' willingness to use the internet or use these social media platforms," he said. "But in an era where $1.4 billion was spent on political advertising in the 2016 campaigns -- and that number [is] only going to go up -- there needs to be equality between traditional radio and broadcast and social media and internet political advertising."

If Facebook, Twitter and Google were to be regulated, that could be one way to hold them accountable for their oversights and force them to be more transparent -- something they roundly failed to do both during and after the 2016 election. Of course, as is often the case with any proposed legislation, it could take some time for the Honest Ads Act or other bills like it to become law. Or it could never happen at all.

There are experts like Paul Levinson, a professor of communications and media studies at Fordham University, who believe that might be for the best, since they don't see how the government can regulate these companies and what people share on their platforms without infringing on First Amendment rights. After all, not everyone who posts or advertises on Facebook, Twitter and Google is a Russian troll.

"I don't see Congress trying to legislate an algorithm, because that is beyond the regulatory reach and competence of the government." -- US Representative Adam Schiff (D-CA)

It's possible that in 2018 Congress will propose more bills like the Honest Ads Act that are designed to curb tech companies' influence in politics. The efforts to contain them thus far have been bipartisan, suggesting that social media's road to federal regulation may be more than a pipe dream for the government. Representative Adam Schiff (D-CA), ranking member of the House Intelligence Committee, told Engadget that Congress needs to exercise much more oversight to understand how software algorithms used by Facebook, Twitter and Google work.

But he doesn't see "trying to legislate an algorithm, because that is beyond the regulatory reach and competence of the government." He said that because technology changes so quickly, "any prescriptive laws Congress might pass along such lines would likely be made obsolete" in no time. "That doesn't mean that government should not act where we can, however," he added, "particularly if the current technologies leave us vulnerable to foreign manipulation or have the effect of deepening divisions in our country."

Schiff said there are representatives and senators from both parties interested in legislation that would regulate political-ad disclosures on social media. He also said that, down the road, it will be necessary for the intelligence community to work closely with tech companies to prevent any future attacks on our country's democratic process.

"When the intelligence community gathers information that a foreign adversary is exploiting the use of these platforms in a clandestine way to influence our elections," he said, "it should have a mechanism like we use in the counterterrorism context to share that information with the technology companies." Schiff said that ultimately, these joint efforts between the government and tech firms will be crucial to prepare for any upcoming elections.

"When the intelligence community gathers information that a foreign adversary is exploiting the use of these platforms in a clandestine way to influence our elections, it should have a mechanism like we use in the counterterrorism context to share that information with the technology companies."

He said that, as part of the Intelligence Committee hearings, he's asked Facebook, Twitter and Google to create a joint report on how Russia played their systems, so that the committee can be fully informed before making any recommendations that might affect how they do business. "Although the companies have yet to commit to such a report," he said, "it is my hope that they will do so."

If a bill like the Honest Ads Act does become law, tech companies could be prone to government fines if they don't follow set regulations. That would be akin to when US wireless carriers violate consumer disclosures and the FCC has to step in, often slapping them with hundreds of millions of dollars in fines.

What's clear is that the government isn't interested in regulating your tweets or Facebook posts about how much you love or hate Donald Trump. (That would be a clear violation of the First Amendment.) Instead, the committee simply intends to keep a better eye on the political ads that you see on social media, to ensure that foreign agents aren't interfering in our elections. This doesn't mean you, the user, can be out there promoting hate speech on your timeline, since Twitter or Facebook might take it upon themselves to ban you. (Unless you're the president of the United States, of course.)

Levinson said that, generally speaking and no matter the reason, the US government shouldn't try to regulate Facebook, Twitter, Google or any other social media company because "they have no idea what they're talking about" or how the internet works. If anything, he said, these tech giants should be working harder on self-regulating, which would mean depending less on algorithms and more on humans.

For Levinson, the ideal system to fight bots promoting sketchy political ads and fake news would be to identify fake, ill-minded accounts more quickly and to cancel them immediately. He also said there needs to be a better way to distinguish fake news from real articles or a post from people simply expressing their opinion -- even if certain people don't agree with it. In order for that to happen and be successful, though, Levinson said algorithms from Facebook and Twitter need to experience some trial and error before they can be perfected. That's why you sometimes see bogus content slip through the cracks.

Levinson added that it's hard to say how the government could enforce rules on social media companies, but if it comes close to infringing on people's First Amendment rights, that would cause some civil issues. Levinson said he imagines there would be thousands of cases in the courts, noting that he believes any regulation could be a real threat to the internet as we know it. "Everyone's so concerned about net neutrality. I don't really care about whether corporations dominate or don't dominate, there's no way any corporation's going to tell anyone what they can or can't say," he said. "But I am concerned about the government dominating and destroying the essence of the internet."

Regardless of what happens, one thing is indisputable: The government and these tech companies will need to work more closely in 2018 and beyond, in order to ensure that history doesn't repeat itself. It won't be easy, because there are business models and, most importantly, people's First Amendment rights at stake. Hopefully Facebook, Twitter, Google and the government will figure out the best way to keep Russian (and other foreign) trolls and bots at bay. Otherwise we'll be talking about this again in 2020.

Check out all of Engadget's year-in-review coverage right here.