The one-cable future of gadgets: simpler, but still confusing

For such a quiet tech show, this week's Computex in Taiwan may have been a watershed moment that will affect nearly every PC, phone and tablet you'll see in the next few years, if not decade. The new USB Type-C port may have debuted on flagship devices like Apple's single-port new Macbook and Google's Chromebook Pixel, but the new, smaller, reversible kind of USB is shaping up to be the connector of the future. This week ASUS joined the USB-C party, and in a reassuring vote of confidence, Intel announced that its newest iteration of Thunderbolt will take the same shape. Thunderbolt 3.0 will, at a minimum, double the data speed found on USB-C cables. It might not work wirelessly just yet, but the single-cable future is coming. However, change isn't always easy.

Other than a standard headphone jack, the new MacBook has just one USB-C port.

Sure, tech companies adopting yet another kind of port doesn't send shivers down your spine. But what USB-C can do is worth getting at least a little excited about: a single wire that delivers data, power and display signal all at the same time. It's all done through a connector that's roughly a third of the size of the decades-old USB port you're used to. It's also reversible, and because power can flow both ways, the host device (say a laptop) can both charge other gadgets or be charged by them.

In short, connecting and charging nearly any gadget is about to get real simple. Like the mid-'90s introduction of USB, which effectively removed serial and parallel ports from the back of PCs and laptops, USB-C could do the same for all things in mobile computing, but to an even larger extent, replacing cables for power, data and video.

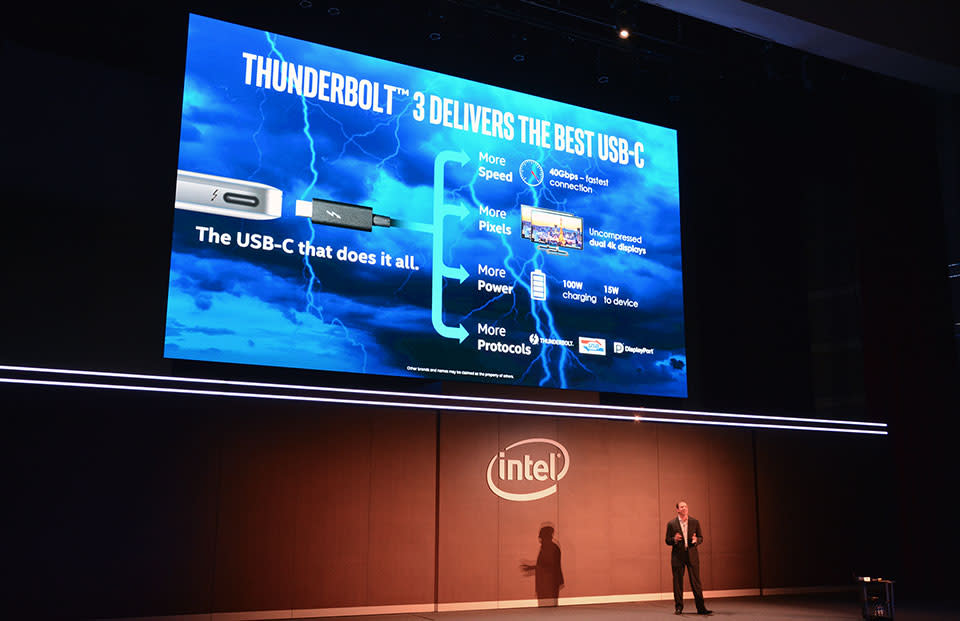

Thunderbolt 3: looks like USB-C, but better in a few ways.

But nothing's ever that simple and not all USB-C is created equal. In fact, USB-C is really only the physical shape of the port and connector. The extent to what the cable can do depends on the hardware you're connecting it to, and what version of USB it's using. There are already USB-C devices (like Nokia's N1 tablet) with "only" USB 2.0 capabilities. Then there's Apple's new MacBook and the latest Chromebook Pixel, which use USB 3.1 Gen 1 spec, with data speeds up to 5 Gbps. This part alone is confusing because the first-generation USB 3.1 specification is pretty much exactly the same as USB 3.0. (Ars Technica sums up the confusion well here.) Finally, there's the full 10 Gbps data-slinging power of second-gen USB 3.1, which will arrive on next-generation machines. Just because it has the tiny USB-C port on the end, it doesn't mean it'll be able to charge the device you're plugging it into, or offer the highest data speeds. There's a danger that manufacturers could very easily mislead buyers.

When Intel set out to design Thunderbolt 3, it wanted both double the data rate of Thunderbolt 2, while also settling on a smaller form factor. USB-C fit the bill. Better still, it already housed space for "alternate mode." This is where companies are able to transmit other things besides data and power, making it ideal for the additional tricks Thunderbolt could bring. In short, Intel already had a winner in USB-C; there was no need attempt to create another type of cable.

If you're doing a lot of data-based heavy lifting, Thunderbolt has usually made sense.

But while Intel's new Thunderbolt 3 will have a USB-C connector, those accessories and cables won't work on the existing 12-inch MacBook or the Chromebook Pixel. The chipmaker also has two different types of Thunderbolt 3 cables incoming: a passive one that'll be cheaper than Thunderbolt cables of past, yet will still offer double the maximum speed of USB 3.1, and an "active" cable that includes signal-boosting chips to double (again) data rates. Even checking to see if a cable does or doesn't have a lightning bolt emblazoned on it won't make everything clear.

Isn't Intel adding to the confusion? "We also think there needs to be identification across these (different kinds of USB-C cables) in general," explained Intel's head of Thunderbolt marketing, Jason Ziller. 'We're also considering a secondary identifier for our active cables."

USB-C sockets may not replace everything, however. The original USB port can deliver everything included in the USB 3.1 specification. In TVs, desktops and other devices, where size and reversibility are less of an issue, there's arguably less impetus to change to USB-C. Also, sometimes smaller isn't better. MHL President Rob Tobias explained to me that the newer USB-C ports simply aren't as easy to plug in -- when reaching around the back of a TV, an HDMI or older USB port is far easier to find by feel than a less-than-thumbnail-sized USB-C socket.

"The port could be everything to everybody."

It makes good business sense for Intel to unite around a common standard, if only because of production scale. Apple may have a history of proprietary cables and ports, yet it's also fallen in love with the slender USB-C form factor. Intel's Kirk Skaugen mentioned in his Computex keynote that there are around 30 PC designs incoming with Thunderbolt 3 -- and that's not counting devices that merely feature standard USB-C ports. Then there are the smartphones already packing the new USB port in China -- expect to see plenty more of those as well. As Intel's Ziller noted: "The port could be everything to everybody. It has the superset."