How to make a CES keynote

Last night, director Michael Bay made an abrupt stage exit during Samsung's day zero CES press conference. It was awkward, but little more than a square of toilet paper on the bottom of a tennis shoe compared to last year's Qualcomm keynote. A bizarre mix of stilted theatrics, celebrity appearances and product demos, the presentation was like nothing we'd ever seen -- until we took a look back. Qualcomm may have jacked its keynote up on steroids, but many of the tricks it pulled out were already tried-and-true standards. As Sony's Kaz Hirai prepares to kick things off at CES 2014 this morning, we reflect on 20-plus years of innovative speeches, futuristic predictions and just plain strange behavior.

This is how you make a CES keynote.

Step 1: Think big

John Sculley with Apple's Newton PDA (Photo by Marty Katz//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

When former Apple CEO John Sculley took the stage at the 1992 Winter CES, he set in motion a decade of digital divining by industry bigwigs like Aereo champion Barry Diller and Sony CEO Sir Howard Stringer. Sculley presented a bold vision of the future not only for the US economy and workers on the whole, but also for Apple's future. His was a world where hand-held devices would lead to a fundamental shift in the way we work and learn. He saw computers, and PDAs specifically, as "revitalizing America's role" in the global economy by making everyone more productive. The eventual offspring of this line of thinking was the ill-fated Newton. Of course, Apple would eventually return to the idea of a portable computer that embraced many of Sculley's ideas, but his predictions weren't exactly spot-on.

Sculley's not alone. Many of CES' keynote speakers have painted pictures of the future that were either ill-timed or just plain off. Michael Bloomberg kicked off the 1997 CES with a speech that focused on a new era of digital media distribution. He foretold a robust publishing industry, where writers were in higher demand and readers received the news on digital broadsheets. "The newspaper of a few years from now is made of cloth with transistors hidden in it and essentially a cellular phone with a battery hidden it there as well," he said.

One year earlier, Compaq CEO Eckhard Pfeiffer spoke of a robust connected home becoming the norm in 2000. His theoretical abode had a computer in every room, each tailored to the needs of its user. In the kitchen, a touch- and gesture-based computer would bring the man of the house CNN Headline News, email, fax and the day's appointments while he sipped his coffee. In the bedroom, his wife would connect with her doctor through a large-screen PC that also provided weather alerts and restaurant reviews for an upcoming trip to China. Meanwhile, his teenage daughter would connect to her friends in Germany via her I-phone (that's a capital "I" for internet).

Step 2: Announce something

Bill Gates first appeared on the CES stage in 1995, and in 2000, he gave his first CES kickoff keynote, beginning a 12-year run for Microsoft in that slot. In just over a decade, he and his successor, Steve Ballmer turned the opening night talk from a look at tech's crystal ball into a platform for launching new products, services and ideas. In 2000, Gates introduced the company's new Pocket PC and Reader e-book software. The following year, he upped the game showing off the Xbox and teasing "the future of gaming." Some of these talks were more product heavy than others, but in the time that he was at the helm, Gates announced and demoed everything from smartwatches to internet-connected TVs and HP's aptly named TouchSmart PC.

It wasn't all about gadgets during Microsoft's keynote reign, however. When Ballmer took over in 2009, he announced availability of Windows 7 beta in addition to Windows Live partnerships with Dell, Facebook and Verizon. The following year, Microsoft gave the audience a glimpse at what would become Kinect. That focus on product releases took a turn for the dramatic in 2013, when Qualcomm's Dr. Paul E. Jacobs took to the stage with a smattering of disparate cultural personalities to unveil its latest processor, the Snapdragon 800.

Step 3: Hire a celebrity

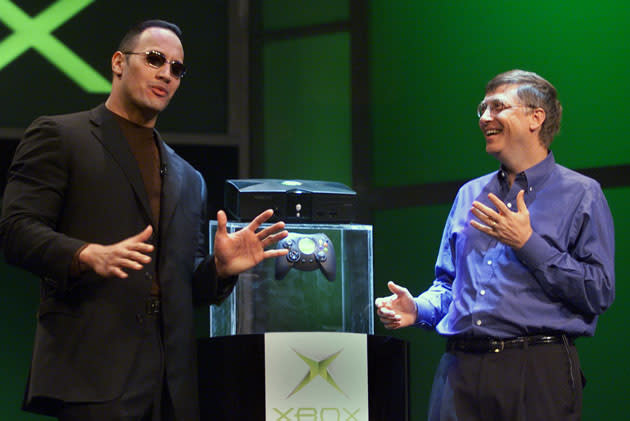

Bill Gates and the Rock show off the Xbox (Photo by Jeff Christensen/Liaison)

With a cast of characters like Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Pacific Rim director Guillermo del Toro, Maroon 5 and even Big Bird, you'd be forgiven for thinking last year's keynote felt more like an incredibly intricate high school production of Xanadu than a self-serious press conference. While Jacobs' state of the industry addresses was by far the most star-studded to date, employing celebrities for the occasion isn't new. Gates enlisted Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson to show off the Xbox in 2001. In 2004, Jay Leno joined him in introducing MSN Video, followed by Conan O'Brien in 2005. To mark his last appearance as the opening keynote speaker in 2012, Ballmer sat down for a conversation with Ryan Seacrest. The following excerpt from that interview demonstrates just how awkward these cameos can be.

Seacrest: I like that. When you said Metro you looked at me in a strange way, or I thought. Is it the jacket, or the sweater, or the combination?

Ballmer: I was going to say it's a new design and a new year, but you take it from there, for Microsoft and Ryan.

Seacrest: I'm your mascot.

Step 4: Man up

Steve Ballmer crashes the Qualcomm keynote (Photographer: Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

As in the boardroom, so on the CES stage. Over the past 20 years, only four of 63 headlining keynote speakers have been women. Of course, Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer is slated for a talk of her own on Tuesday and Facebook's Carolyn Everson will return for her second appearance during a panel discussion Wednesday, but all of their fellow speakers share two things in common. You guessed it: an X and a Y chromosome. This may not come as a shock to those who follow the tech industry closely, but it's a particularly vexing state of being for a conference (and an entire market) that thrives on innovation and change.

Step 5: If all else fails, get weird

Lead image: AP Photo/Julie Jacobson