Self-healing 3D-printed gel has a future in robots and medicine

The hydrogel is soft, yet strong and responsive, and it can be formed in LEGO-like blocks.

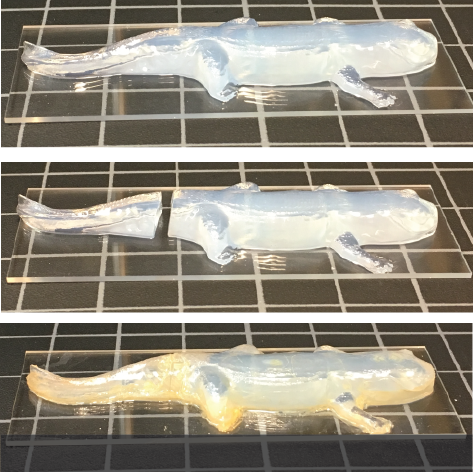

Robots might be a little more appealing -- and more practical -- if they're not made of hard, cold metal or plastic, but of a softer material. Researcher at Brown University believe they've developed a new material that could be ideal for "soft robotics." It's already demonstrated that it can pick up small, delicate objects, and it could form customized microfluidic devices -- sometimes called "labs-on-a-chip" and used for things like spotting aggressive cancers and making life-saving drugs in the field.

The 3D-printed hydrogel is a dual polymer that's capable of bending, twisting or sticking together when treated with certain chemicals. One polymer has covalent bonds, which provide strength and structural integrity. The other polymer has ionic bonds, which allow more dynamic behaviors like bending and self-adhesion. Together, the polymers create a material that is soft, strong and responsive -- ideal for creating a soft, robotic grip.

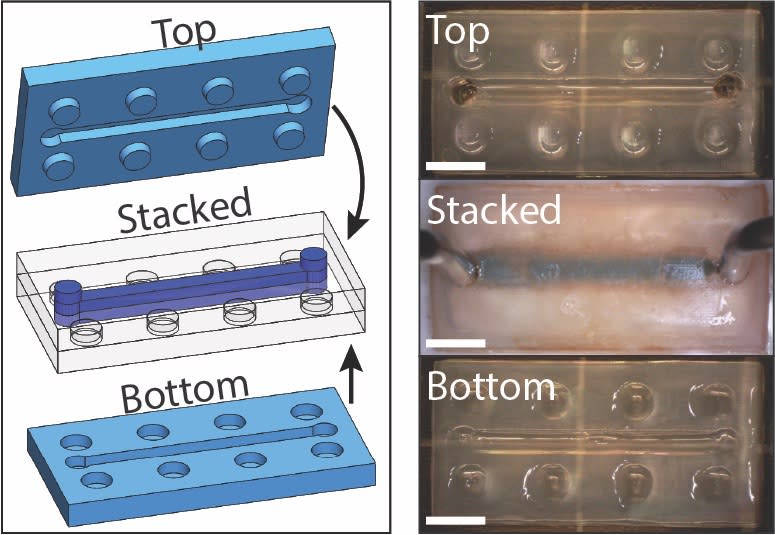

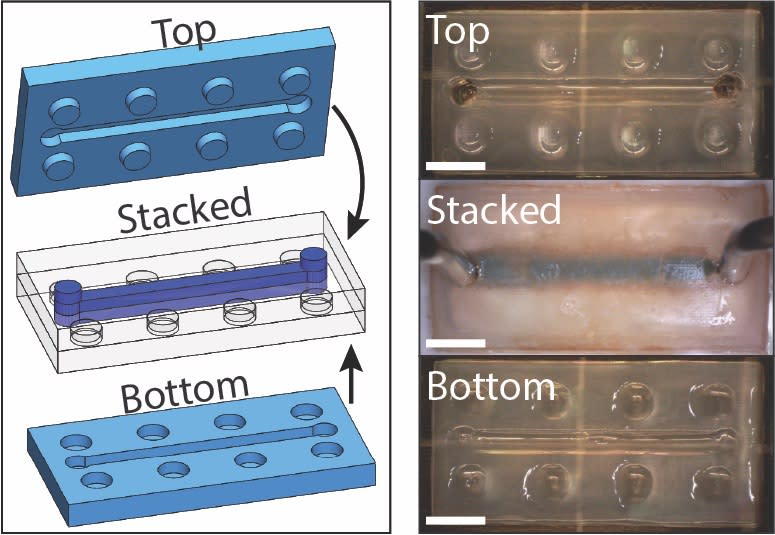

The hydrogel could also be a promising base for microfluidic devices -- used for everything from cancer treatments to liquid-based watch tech and detecting explosives. Until now, it's been hard to pattern hydrogels with the complex channels and chambers needed in microfluidics. But because this new material is 3D-printed, it can be made in stackable LEGO-like blocks, and "complex microfluidic architectures" can be incorporated into each block. These could create a type of modular system in which blocks with different microfluidic channels could be fit together as needed.

The material isn't quite ready for use. Researchers say they're still tweaking the polymers to get even more durability and functionality. If they succeed, this could make building soft robotic components and labs-on-a-chip as simple as snapping together LEGO pieces -- or at least significantly easier.