Earth's radio signals may be protecting it from space radiation

Take that, Van Allen belts

The Earth's atmosphere bears precious little resemblance to what it looked like at the start of the Industrial Revolution. As radio technology has advanced and spread, the signals that transmitters produce -- specifically the Very Low Frequency (VLF) variety -- have changed the way that the upper atmosphere and the Van Allen Radiation Belts interact, according to a study recently published in the journal Space Science Reviews. In effect, these radio waves may be enveloping the globe like an electromagnetic comforter, protecting it from satellite-frying space radiation.

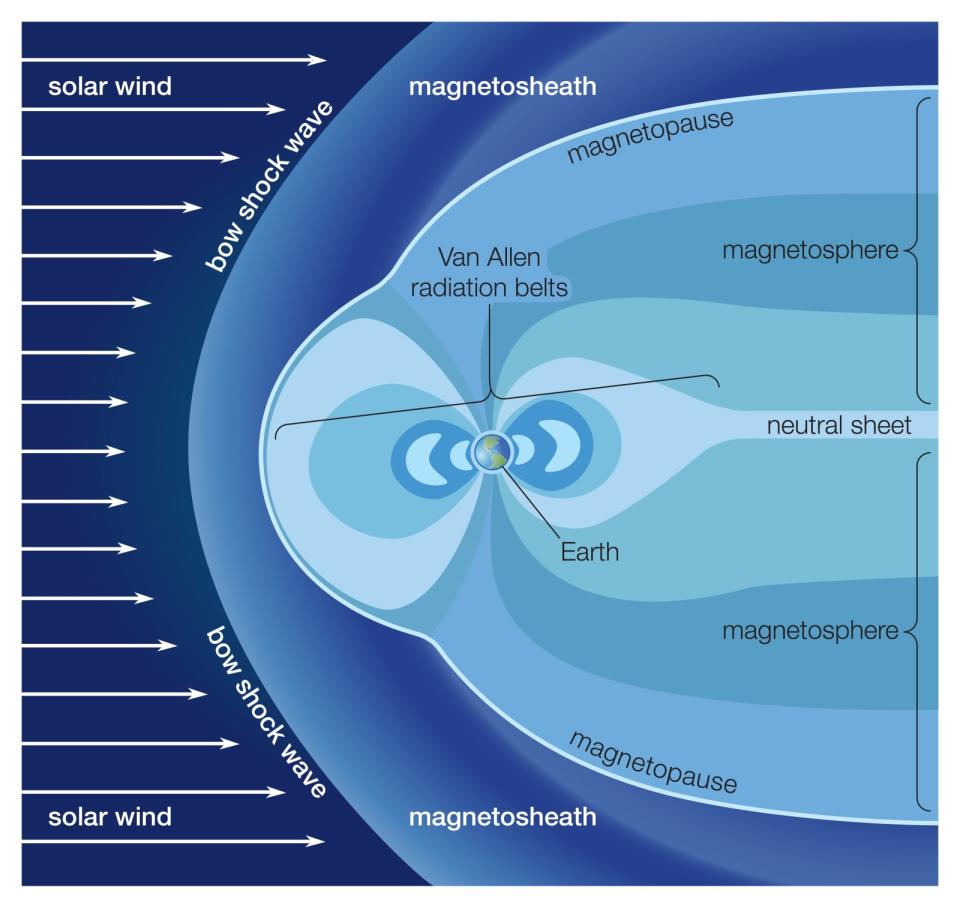

The Van Allen Belts are a pair of zones where high-energy particles blasted out by the Sun become entangled in the Earth's magnetosphere, forming a pair of fluctuating bands that encircle the Earth. Should the belts fluctuate into the path of an orbiting satellite, their energetic particles can easily fry the satellite's electronics -- like a natural EMP.

"The conventional wisdom is that the inner edge of the outer belt kind of moves in and out as the atmosphere—especially ionosphere and plasmasphere—grows and shrinks," says Phil Erickson, a space plasma physicist at MIT, told Popular Science. Well, recent observations from the Van Allen Probes, a pair of heavily shielded spacecraft that monitor the belts, suggest that these fluctuations are being diminished by what appears to be humanity's use of VLF radio transmitters which are often employed in military communications and navigation.

Per the Space Science report, statistical data suggests that the Van Allen Belts have been getting pushed steadily back from the surface of the planet since the 1960's, about when VLF radio technology was first introduced. More recently, even when a 2015 solar storm was strong enough to strip back the plasmasphere like a banana peel, the Van Allen belts stayed in place.

The Van Allen Probes - Image: NASA

This is likely because, the study argues, the radio signals are deflecting incoming solar radiation back into space before they can be captured by the Earth's magnetic field. However, the VLF waves aren't energetic enough to deflect heavier solar emissions, like protons, and can't protect against the effects caused by significant solar storms.

Still, the effect is noticeable enough that the US Navy has made plans to launch the DSX satellite later this year, which will study whether an onboard VLF transmitter is sufficient to protect spacecraft from interstellar radiation. If it proves successful, the first crew to Mars may be able to leave their supply of Rad-X behind.