How Valve's secret meeting got devs on board with Steam VR

Alex Schwartz expected robes. His development studio, Owlchemy Labs, received a cryptic email from Valve, one of the largest and most mysterious companies in the gaming industry, on an otherwise normal day in October. The message contained a secrecy agreement, plane tickets and the vague assertion that this was all about something related to virtual reality. Owlchemy responded with suspicion and intrigue. "What the hell is this? Who's coming? What is this all about?" Valve responded, "We can't say anything more. Just come."

So, Owlchemy did.

"I kind of expected to enter a room where everyone had their heads down, wearing hoods and you part the curtains and hear, 'We've been expecting you,'" Schwartz said. Instead, when the Owlchemy co-founder arrived at Valve's meeting place, he was ushered into a room full of developers from Google, Cloudhead, Bossa and other companies. And then Valve dropped its bombshell announcement, that it was building virtual reality hardware. We now know that it was specifically talking about the Vive, Valve's stunning VR hardware collaboration with HTC.

Owlchemy had an established relationship with Valve: Its games -- Snuggle Truck, Jack Lumber, AaaaaAAaaa! -- were already on the company's digital distribution service, Steam, and the two had met up at the Boston VR Jam in May. Valve wanted the teams in this secret meeting to create experiences for its new headset, in time for the 2015 Game Developers Conference in the first week of March. Owlchemy was all in.

"We basically came up with an idea for a new IP right there on the spot," Schwartz said. "But the problem was, all of us are remote."

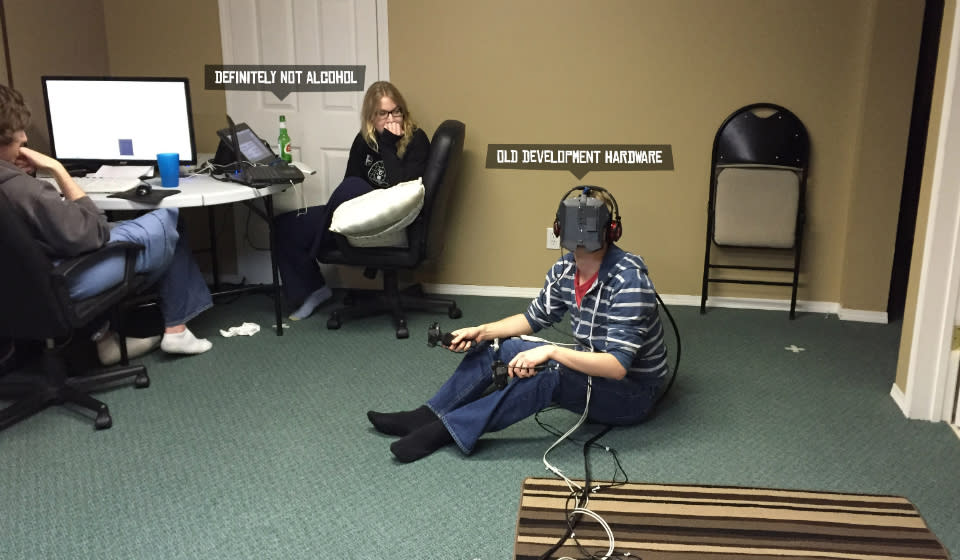

From left: Carrie Witt, Devin Reimer, Graeme Borland and Alex Schwartz

Owlchemy is spread across North America, from Boston to Austin to Winnipeg. Keeping with the trend of odd and slightly shady experiences, it solved this issue in a unique way: The studio's four core members (CTO Devin Reimer, lead artist Carrie Witt, developer Graeme Borland and Schwartz himself) decided to lock themselves in a basement in the frozen Canadian tundra for one week straight. The location was partly out of necessity; Reimer couldn't relocate as easily as the rest of the team, since his wife was pregnant and unable to travel to the US.

"She was getting dangerously pregnant at the time that we were thinking of making the game," Schwartz said. "To accommodate [Reimer], we decided we would all go up to his house in Canada, not even in Winnipeg, which is like the worst place to live in the entire universe, but an hour outside of Winnipeg. So it's like, find the middle of nowhere, and then you're just kind of in the arctic tundra of Canada with nothing around."

"It felt like we had something that no one else did, and that we were the first to see something that was so freakin' cool."

Turns out, it was a wonderful space for Owlchemy to create its first VR experience for the Vive. They had internet access, a dev kit and space to work, and the ideas started flowing. They ended up with Job Simulator: The 2050 Archives, and that game's first world, a cartoony kitchen where players prepare food -- or just mess around with all of the ingredients and tools. By the end of the week, Owlchemy had the core game down. Their time in the bunker was filled with positive vibes, rather than the spiral of self-doubt and failed iterations that usually plague prototyping stages, Schwartz said. "We're just super thrilled."

Plus, Owlchemy felt like it was in on the ground floor of something truly revolutionary. Schwartz compared working with the early Vive dev kit with how it must have felt to receive the first iPhone before it launched. It wasn't pretty, but it was incredible.

"It was like, wires hanging out of it; all this shit was broken and we had to tape stuff together," he said. "We had a piece of cardboard stuck in the controller system because the USB cable kept wiggling out. But it felt like we had something that no one else did, and that we were the first to see something that was so freakin' cool. Honestly one of the coolest development experiences of my life was working on that headset early for Valve. We were just really proud to be able to do that."

One of the most notable aspects of the Vive, for Owlchemy, was that it didn't cause motion sickness. They had the perfect test subject in Reimer's wife, Melissa: She was easily nauseated by VR in general, often having to lie down for half an hour after just a few minutes of playing, plus she was eight months pregnant. With twins.

"Likely the worst-case scenario for nausea," Schwartz said. "And she had no negative effects at all. When she took off the headset for the first time, she said, 'Now I have to go sit down,' then paused, and then said, 'Wait, no, I don't have to go sit down.'"

After that first, chilly week, Owlchemy spent the next month and a half polishing Job Simulator's kitchen demo from their own remote locations. The goal was to make every interaction as lifelike as possible -- when Schwartz showed the game to his wife for the first time, she picked up a plate and threw it on the ground, expecting it to break. It didn't.

"This is garbage," she said (lovingly, probably). After that, the first item on Schwartz's list of things to fix was, "make plates breakable," followed by items like, "make knives cut" and "make pans swing on their hooks." The world of Job Simulator is cartoonish, but making things feel "real" in VR isn't about realistic objects or environments, Schwartz said:

"A feeling of being present in a space is really important. Trying to go for 'realism' from an artistic standpoint is very tough in 2015 VR because we're not quite there. ... What we've found is that 'place' feels alive when you feel that sense of presence there, if the world reacts like you think it should. And the lighting of the world gives your eye cues that it's a realistic place."

The Vive makes virtual reality work for the easily nauseated and Sony execs alike.

Now, Owlchemy is working to build a full version of Job Simulator, with more than just kitchen chores. Schwartz isn't sure how many jobs will be in the final game; the team is trying out new ideas and seeing what sticks. It won't be exclusive to the Vive, either -- Owlchemy wants Job Simulator on as many VR devices as possible, as long as they have "hands," the term he uses to describe dedicated input systems. This excludes the Oculus Rift, for now.

"We've talked to Oculus and they're not sure what is going on with input still," Schwartz said. "So we're kind of waiting on that. I'll be completely honest: I think it would be a mistake to launch consumer VR products without any input. ... There's nothing fun about looking around in a cartoon kitchen. It's all about fucking around in it. And you can't do that unless you have your hands, and that magic and that sense of wonder."

Oculus, for its part, agreed with Schwartz. "Input is still one of the critical missing pieces, and we don't have that much to announce today," Oculus VR Product VP Nate Mitchell said in January. "But what I can say is it's something that we are super dedicated to tackling."

One VR company that Owlchemy is talking to is Sony, with its Morpheus headset and Move motion controllers. Much to Schwartz's fanboyish pleasure, Sony Worldwide Studios President Shuhei Yoshida tried out Job Simulator at GDC last week.

"He loved it," Schwartz said. "He was giggling the whole time and throwing things around. ... The childlike wonder you can get out of someone when they go into this cartoon kitchen and just start throwing things around and breaking eggs and making sandwiches, that's the coolest part."

Thanks Valve, @OwlchemyLabs and @CloudheadGames, I had a fun, fun VR experience at Valve's booth #SteamVR pic.twitter.com/STnFgSZbq2

- Shuhei Yoshida (@yosp) March 6, 2015

[Image credits: Owlchemy Labs]